APPC Report #10, March 1997

About the author

Kathleen Hall Jamieson is Professor of Communication and Dean of the Annenberg School for Communication and Director of the Annenberg Public Policy Program of the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of Eloquence in an Electronic Age (Oxford, 1988), Dirty Politics (Oxford, 1992), and Packaging the Presidency (Oxford, 1996). She is the co-author (with Joseph N. Cappella) of Spirals of Cynicism (Oxford, 1997).

Executive Summary

This report asked, has the level of civility in the House of Representatives changed? If so, how, why, and what can be done about it?

DEFINITION

In Congress, comity is based on the norm of reciprocal courtesy and presupposes that the differences between Members and parties are philosophical not personal, that parties to a debate are entitled to the presumption that their views are legitimate even if not correct, and that those on all sides are persons of good will and integrity motivated by conviction.

BACKGROUND

The discussion of civility and Congress occurs in a climate in which the public perceives that incivility is a pervasive social problem, trust in institutions is low, and Congress is not held in high regard.

The background report is predicated on the assumption that strong partisanship and civility are not mutually exclusive. Pleas for civility are not calls for blurring partisan differences.

Incivility has provoked concern throughout the history of the Congress. The Rules of the House and the precedents interpreting them are designed to create a climate conducive to deliberation.

By curtailing the offending member’s right to speak until it is determined whether his words will be struck from the record, the rules also dampen the likelihood that the tensions will escalate. The process of taking down the words focuses the House’s attention on the nature of inappropriate discourse; striking words from the record expresses collective disapproval; requiring the consent of the body before the offending Member is permitted to re-enter the debate establishes a formal mechanism for reincorporating those who have breached decorum into the deliberative community.

This process also minimizes the likelihood that a person attacked will respond in kind. By focusing debate on the topic under consideration rather than on the advocates themselves, the rules depersonalize the discourse of Congress. So, for example, speakers do not address each other but rather the chair (“Mr. Speaker”), they speak of each other as representatives of a state (“the gentlelady from…”) not as spokespersons for a party or a position; the person recognized by the Chair determines whether, if, and to whom he or she is willing to yield.

The taking down process makes institutional sense only if the Chair is perceived as even-handed and consistent and the Members of both parties are presumed to share an interest in maintaining comity. By contrast, if the Members of each party treat the taking down process as a partisan act, the process becomes a meaningless exercise that will inevitably produce a result consistent with the wishes of the Majority party. Depending on what suits its interest, the majority party can successfully appeal any ruling of the Chair or table any motion to appeal a ruling. If a Member of the minority objects to striking the words, the majority has the votes to strike.

In this scenario, any ruling by the Chair against the words of a member of the minority would be upheld and any against a Member of the majority, voided. The request that the Member be permitted to proceed in order can be politicized as well.

The taking down process is most effective when the offending Member recognizes what was unparliamentary about the statement, asks unanimous consent that the words be withdrawn, apologizes to the person whose integrity has been impugned, and does not hold a grudge against the person who demanded that the words by taken down.

The process is least effective when: the person demanding that words be taken down is from the other party, the person whose words have been challenged does not understand why, the Chair does not provide a clear and compelling explanation, the opportunity to apologize is foreclosed, and the request to permit the Member to proceed in order is denied. Where the first scenario reduces tension, the second magnifies it. Where the first invites understanding, the second invites pay-back. Where the first instructs the House and the Members in the norms of appropriate discourse, the second is simply punitive.

METHODOLOGY used to answer question, has level of discourse in house changed?

Because the Congressional Record is not necessarily a faithful reflection of what happened on the floor, relying solely on it to determine whether incivility has increased is problematic. So, in addition to studying the Record, we interviewed 11 reporters who have covered Congress for a decade or longer, examined press accounts, and incorporated the assessments of Members who have served multiple terms.

Additionally, we charted demands to take down words and rulings on words taken down from 1935 through 1996. This was done by copying the reports on words taken down from the Journal of the House, checking that record against the one gathered in two Congressional Research Service reports by Ilona Nickels and one report by Republican leader Bob Michel, and conducting a Lexis-Nexis search of the Congressional Record from 1985-1996.

For the 1985-1996 period, we also searched the Record for indications that debate had been disrupted. The two indicators we chose were uses of “The gentle/man/lady/ member will suspend” and “The House will be in order.” In September 1996, Republican Members began using points of order instead of demands that words be taken down to object to Democratic references to activities in the Ethics committee. The search for “X will suspend” captures these exchanges. It also catalogues the dispute over Democratic use of the front page of the New York Daily News as a chart. In that altercation, the Chair asks that the gentleman suspend a total of nine times. Although not an invariable predictor of hostile exchanges, requests to suspend were exceeded in reliability only by demands to take down words. For example, the search permitted us to locate such exchanges as:

X: “I just want to make sure the gentleman sticks to the facts.”

Y: “The gentleman will not impugn my remarks in that way at all. The gentleman from …does not have the time, and he has no right to do that to this Member.”

Speaker pro tempore: “The gentleman (Y) from… will suspend.”

Y: “Mr. Speaker, that should not be done.”

Speaker pro tempore: “The Chair advises the gentleman (Y) from …. that the gentleman will suspend.”

Y: “Let the gentleman(X) from … have his own time. The gentleman from ….wants to take cheap shots, and he can take them on his own time. The gentleman knows exactly what he did.” Speaker pro tempore: “The gentleman (X) from… will suspend. Gentlemen, all Members need to keep their statements to the Record and focused on the issue at hand.”

A search of the word “admonish” yielded less precise results and was discarded. Calls for the House to be in order were sought out as a crude measure of the amount of noise and distraction in the Chamber at different periods. (For example, “The House will be in order. The gentlewoman deserves the courtesy of being heard. The House will be in order.” “Mr. Speaker, the House is not in order, and the gentleman is entitled to be heard. We cannot hear the Speaker.” Speaker pro tempore: “The House will be in order.”) It is likely that back-of-the-chamber conversation increases at the ends of legislative days as Members are awaiting a vote but we don’t have a good reason to assume that the number of those occasions would change dramatically from Congress to Congress.

To chart uses of vulgarity, we searched the Congressional Record from 1985-1996 on Lexis-Nexis using as search words the vulgarisms, profanity, and course language identified by scholars as the ones most commonly used in conversational speech. The comparative analysis of vulgarity in the British House of Commons was compiled by conducting a comparable computer search of Hansard. It is important to note that 95/96 Hansard covers Parliament from Fall 1995 to Easter Recess 1996 and so is not directly parallel to the 104th in length.

To determine whether accusations about lying have changed over time, we summarized uses of words taken down and supplemented that analysis with the results of a Lexis-Nexis search of the Record from 1985-1996. All uses of the word “liar” were classified by such categories as whether they referred to another Member of Congress, a domestic agent but not a Member, a foreign agent, country or ideology.

To see whether the number, content or tone of one-minute speeches delivered at the beginning of the day have changed since the advent of C-SPAN, we examined 1,413 one-minute morning speeches delivered in June of 1970, 1971, 1978, 1979, 1986, 1987, 1994 and 1995. The coding instrument used to assess level of negativity was developed as part of the Campaign Mapping Project at the Annenberg School.

FINDINGS

Ten of eleven reporters interviewed believe that the level of incivility in Congress is higher in recent years.

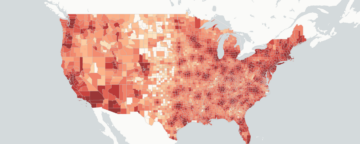

An analysis of demands to take down words and of words ruled out of order from 1935-1996 suggests that incivility was higher in the period 1935 to 1951 than in the period 1980-1996, that the interim was relatively quiet, and that incivility peaked in 1946 and 1995.

Each of those times corresponds roughly to a change in control in the House and Senate at a time in which the White House was held by the other party. Requests for the Member to suspend and demands that the House will be in order also increased in 1995, the first year of the l04th Congress.

A qualitative analysis of uses of “liar” suggests that in the 1940s and 50s, Members were more likely to accuse a foreign enemy of lying and are now more likely to address such charges against the president, a presidential candidate, an opposing party, or each other. A content analysis confirms that discussions of lying have more frequently referred to or been directed at other Members in more recent times (Figure 3).

An analysis of uses of vulgarity suggests that the l04th was less likely to include coarse language than most of the Congresses of the past decade (Figure 4). A comparison of the level of vulgarity in the House and the British House of Commons suggests that the level in the U.S. is somewhat higher.

By four measures then (words taken down, words taken down that go to rulings, calls for the House to be in order and for a Member to suspend), the l04th Congress was less civil than its recent predecessors. By one measure, vulgarity, it was less so. And across the period studied, accusations of lying have become more personal. Focus on these data should not obscure the fact that in the day-to-day deliberations on the floor and in committee civility remains the norm.

The number of morning one-minute speeches has increased since the advent of C-Span from an average of 5 per day in 1970 to an average of 17 per day in 1995 (see Table 5). The number of speeches criticizing the President, the Congress, the Senate or the Judiciary has increased (Figure 5) from fewer than an average of 1 per day in 1970 to an average of 5 per day in 1995.

EXPLANATIONS

Factors contributing to the perception that there has been an increase in incivility include the fact that others are now more likely to reveal the private language of a public figure than they once were and the press is more likely to focus on and hence magnify moments of conflict than moments of compromise and comity.

Partisan discourse is less likely to turn into personal attack when those involved are friends. For this reason, changes that have minimized contact between Members of different parties are cause for concern. These include a decrease in time spent together outside the Chamber (e.g., shorter legislative weeks, increased time in the home district, the demise of group travel and such social activities as Wednesday night poker) as well as in the Chamber (e.g., electronic voting minimizes informal contact on the floor as does the ability to monitor floor debate on C-SPAN). The drop in interpersonal social contact coincides with a rise in partisan intra-party contact in the form of regular meetings of the party caucuses and conferences.

Some situations are more likely to produce incivility than others. These include transitions in control of the Congress when the White House is in the hands of the other party, incidents in which the minority feels abused or the majority obstructed, and occasions when Members or a Member in a leadership position are being investigated on ethics charges. Two forms are more likely than others to be uncivil: one minute speeches and Special Orders. By bracketing the legislative day they can set a problematic tone for deliberation.

Inconsistency in what is taken down makes it difficult for new Members to learn norms and invites charges that the Chair’s enforcement is partisan. Uneven enforcement has occurred when Members have engaged in name calling, used profanity, directly addressed someone out of the chamber, engaged in hissing and booing, told others in the Chamber to shut up, tagged the actions of another as hypocritical, or impugned the motives of the president. It is important to note of course that in the clearest instances either the request or the words will be withdrawn before additional parliamentary intervention. The cases most difficult to call are probably the ones most likely to go to a ruling.

Over time, inflammatory tactics have emerged which skirt the rules. The report illustrates uses of the oblique insult, phrasing an attack as a parliamentary inquiry, use of the parliamentary inquiry to lodge a political point, misstating another’s position, praeteritio, and repeating words to be taken down when asking unanimous consent that they be withdrawn.

Those concerned with increasing comity have developed an alternative range of responses which include actively redefining the rhetorical terrain by reiterating the rhetoric of friendship, transforming confrontation into conciliation, metacommunicating about civility, reframing, de-escalating using humor, refusing to respond in kind, intervening through friends, and bipartisan action or intervention by a person of the offending Member’s party. The report illustrates Members’ effective use of these strategies to minimize tension.

AUTHOR’S RECOMMENDATIONS

Increasing the accuracy of the Record

- Adopt the model of the court system, providing descriptions of visual aides in the Record. This will permit the Parliamentarian’s Office to develop a list of precedents governing visual materials.

- Record efforts to gavel down a Member. Often, what appear to be inconsistent exercises of parliamentary authority would appear less so if the Record showed that the inappropriate behavior was being gavelled down. If this change is made, it would be important to note when the Chair is gavelling to quiet the gallery rather than the floor.

Modifying the rules

- Encourage more parliamentary intervention against unparliamentary language during Special Orders. Change the rules to say that appeals of the decision of the Chair made after regular business hours will be taken under consideration to be voted on at a specified time on the next legislative day. In the meantime, the Member whose words have been taken down will retain the right to speak for the rest of the day. After the vote on the appeal from the ruling of the Chair, if the Chair’s ruling is sustained, permission would be required for the Member to proceed in order for that day.

- When a Member uses unparliamentary language, the words are taken down, stricken from the record and the Member requires permission to regain speaking privileges for the day. There should be some comparable form of penalty for a Member who threatens another Member with violence or engages in an act of violence on the floor, in areas adjacent to the floor, or in committee meetings.

Creating a culture conducive to comity

- When a Member is named, questioned, or referred to by another and requests the opportunity to respond, s/he should be yielded to for response. When a Member plans to criticize another Member on the floor during Special Orders, s/he should as a courtesy notify that Member. In the past, individuals of both parties have assumed that they should be granted these courtesies.

- When one side has yielded to the other, it is courteous to reciprocate when one holds floor.

- When a Member refuses to yield, requests to yield should not continue.

- Words being withdrawn should not be repeated.

- When a Member indicates a willingness to apologize, the apology should be accepted.

In practice

- Increase party vigilance. Members have functioned as parliamentary watchdogs in the past. They have acted aggressively to protect the rights of their party and of its Members. Indeed, when one member retired, he was eulogized by one of his colleagues on the grounds that “For years he served his party, this institution and the country by challenging procedure and process to ensure that the minority voice and opinion would be heard.”

The parties might assign Members of comparable skill to restrain the inappropriate tendencies of their own party. These individuals would be tasked with calming the Member and his/her speech before it oversteps the line, securing recognition to urge a change in the tone of debate and would move to take their own Member’s words down if they were unparliamentary. In the past some Members have performed this function.

This is consistent with a recommendation made by the Speaker in a response to an inquiry about the guidelines for debate: “I have suggested to the Minority leader that each party take a more active role in enforcing proper floor behavior. I fear that if it is left solely to the majority party or the Chair, it will be viewed as a partisan act.”

As both parties proved in the debate over the Ethics Committee’s recommendations on the Speaker in 1997, leaders in caucus can successfully instruct their members to behave decorously in tense situations.

- Focus the attention of reporters on the apologies issued by Members who have breached decorum to increase likelihood that they will receive attention.

- Either eliminate or move the time of one minute speeches.

- Reinstitute the experiment in Oxford Debates.

- Increased vigilance of Speaker and Members.

Since there is no appeal from the Speaker’s recognition or non-recognition, the Speaker can minimize or eliminate the use of inflammatory parliamentary inquiries during the taking down process.

Since Members are to be referred to as the gentleman or gentlelady from…, the Speaker should intervene to caution against use of pejorative nicknames (e.g., “stonewall,” “feelgood”, “closed rule” x) for Members in debate.

To help Members develop a clear sense of the norms, whenever s/he feels that it would not be inflammatory, the Chair should cite precedents and explain the reasoning justifying the ruling.

- It is easier to vilify those one doesn’t know. If social contact increases comity, then increasing the number of activities that bring Members of different parties (and their families) together off the floor should encourage a higher level of mutual respect during floor exchanges.

- The office of the Parliamentarian might assemble a clear, short guide to behavior on the floor which could be given to new members at orientation. It would, among other things, explain the principles governing the precedents and the explicit norms central to maintaining a climate of comity.