During the holidays, many in the press write stories aiming to help readers cope with the blues and other seasonal conditions. But some journalists inadvertently support a myth about the holidays and suicide, or quote well-intentioned sources who should know better.

Despite the fact that the holiday season has some of the lowest average daily suicide rates, some journalists continue to perpetuate the holiday-suicide myth.

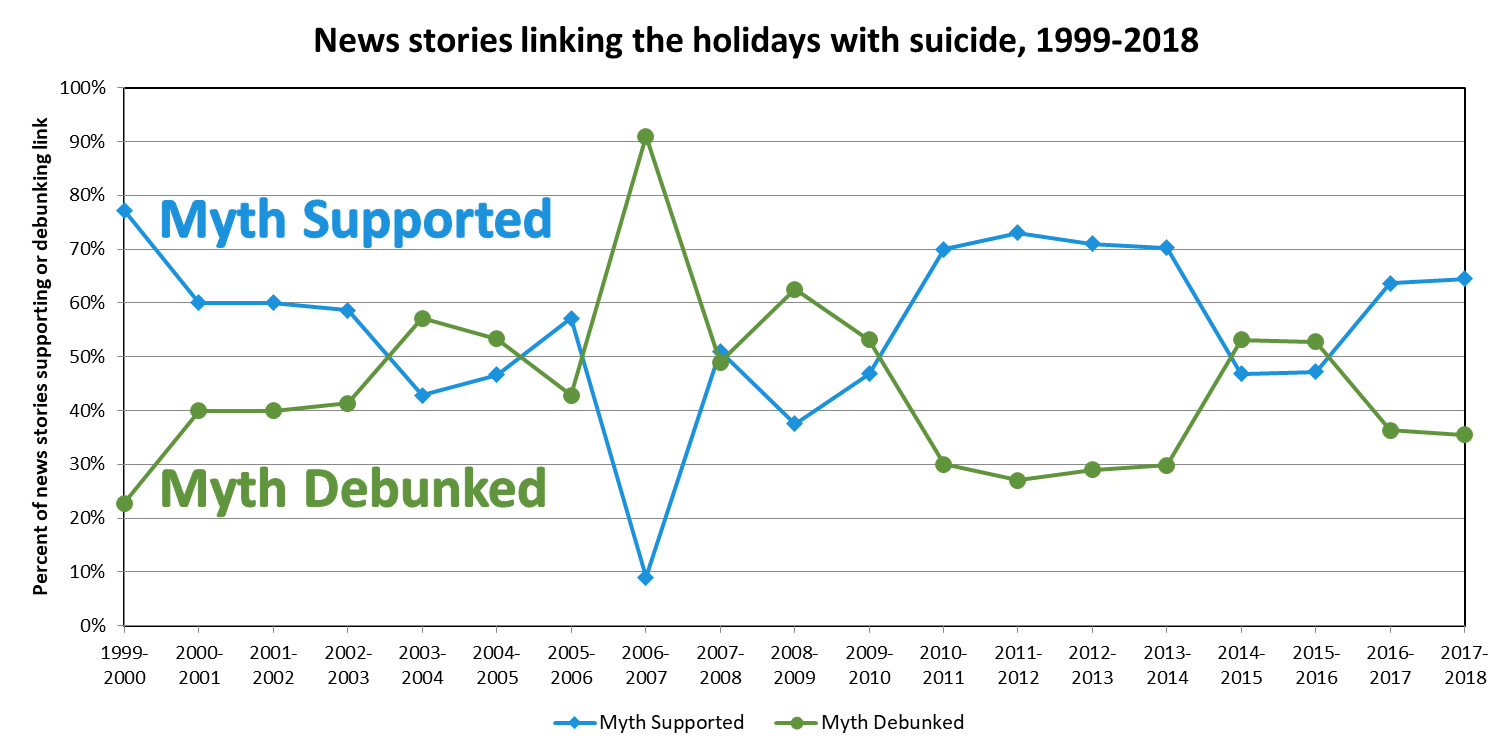

In the 2017-18 holiday season, two-thirds of the print news and feature stories that mentioned both the holidays and suicide drew a false connection between them, according to the latest analysis by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. The analysis was based on stories in the Nexis database and excluded coincidental references.

The result was unchanged from the prior holiday season. Of the 31 stories examined, 65 percent supported the holiday-suicide myth, while 35 percent debunked it. An additional 32 stories made coincidental reference to holidays and suicide and were excluded. (See figure 1.)

“Although many of the stories supporting the myth were published in rural areas, we hope that greater awareness of actual suicide risk will help residents of those regions to better cope with whatever stresses they might experience during the holiday period,” said Dan Romer, research director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC).

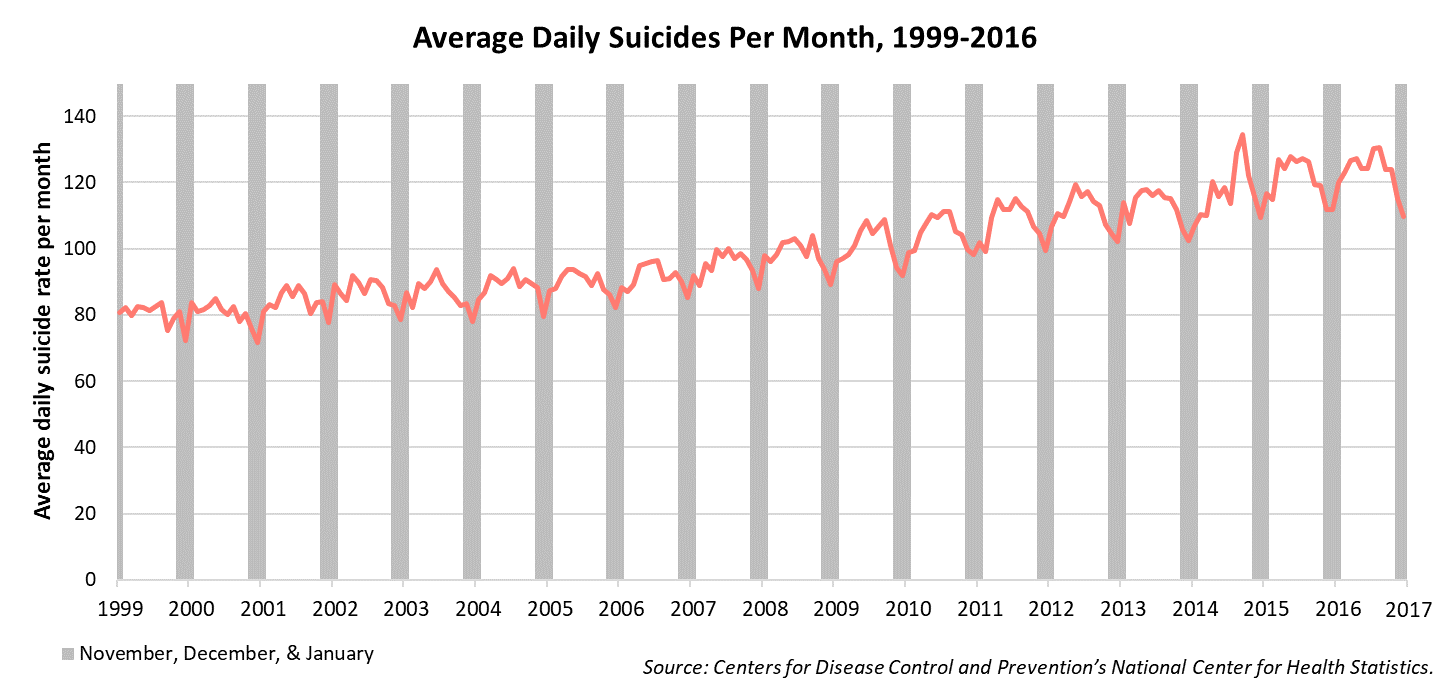

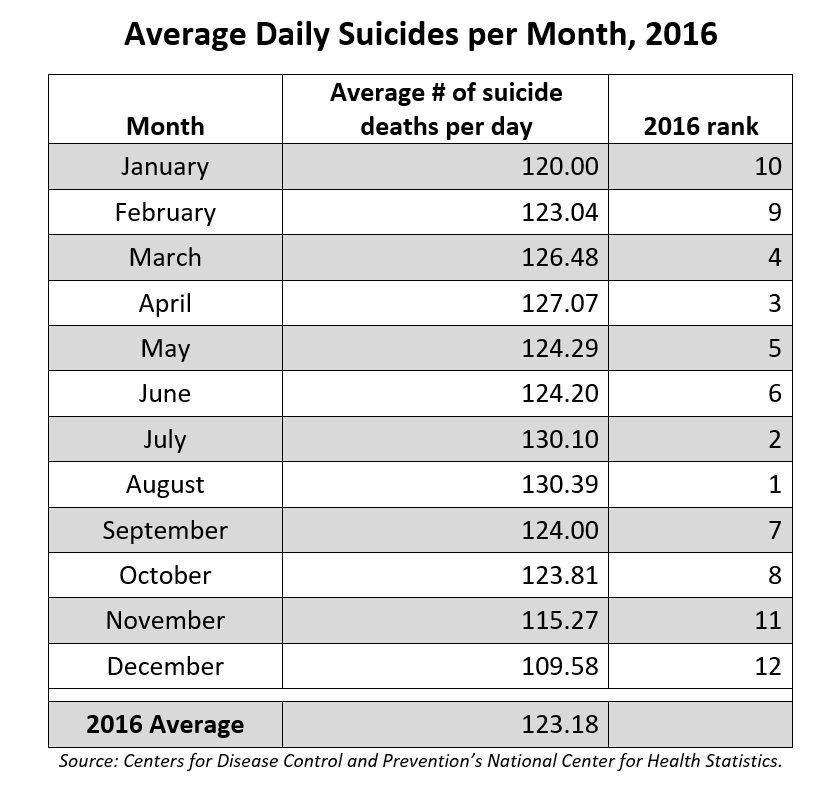

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the holiday months have some of the lowest suicide rates. CDC data from 2016, the most recent available, show that November, December, and January were the lowest months in average suicide deaths per day (11th, 12th, and 10th, respectively). The highest average daily rates are typically in the spring and summer. In 2016, the months with the highest average daily suicide rates were August and July (1st and 2nd, respectively). (See figure 2 and table 1.)

Perpetuating the holiday-suicide myth

APPC has analyzed news coverage of the holiday-suicide myth since 1999 and in most of those years, more newspapers have upheld the myth than debunked it. In only two of those years did more than 60 percent of the news stories that were tracked debunk the myth.

A number of the stories that perpetuated the myth this year were published in local newspapers. Among them:

- A columnist for The Advertiser-Gleam in Guntersville, Ala., wrote: “At Christmas, we certainly have all the accoutrements of having a glowing feeling. There is beautiful music, sparkling array of lights in every direction, excitement of family together … so many things that affect our moods. So, why are there so many suicides during the Christmas holiday?” (Dec. 20, 2017)

- A Wilmington, Del., News Journal story about people struggling with addiction quoted the CEO of a counseling service as saying: “For some, you see an increase in suicide and depression around the holidays because the holidays can be such a difficult time for so many people, especially when the world in inundating you with cheer.” (Dec. 23, 2017)

- A columnist for the Hutchinson Leader in Minnesota wrote: “It has long been observed that the rate of suicides and interfamilial violence goes up during times of traditional family gatherings.” (Dec. 27, 2017)

- A reporter for the Wyoming County Press Examiner, in Pennsylvania, wrote: “Holiday blues is a common problem this time of year, with hospitals and police departments reporting high incidents of suicides and attempting suicides, Luongo [a college counselor] said.” (Dec. 6, 2017)

Giving people the sense that suicide is more likely over the holidays may have adverse consequences, Romer said. For vulnerable individuals who are already contemplating suicide, such news can have contagious effects. This is why the national recommendations for suicide reporting by the news media advise journalists not to promote information that can increase contagion, such as reports of epidemics or seasonal increases, especially when there is no basis in fact.

Getting it right

Other publications large and small debunked the holiday-suicide myth, sometimes while acknowledging the fraught nature of the holiday season:

- In a story on “supporting the struggling” at holiday time, the Gaylord Herald Times, of Michigan, said: “According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it is a longstanding myth that suicides occur more frequently during the holiday season. The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics has reported that the suicide rate is at its lowest in December, with peaks in the spring and the fall.” (Dec. 28, 2017)

- Just after New Year’s Day, in the Riverton Ranger (Wyoming), columnist Randy Tucker wrote about post-holiday melancholy: “It is often a very persistent experience following the holidays, a time when holiday cheer often leads to feelings of isolation. Combined with the depression familiar during the winter months, common knowledge claims suicide rates are highest during the dark days of the New Year – but the opposite is true.”

Journalists helping to dispel the holiday-suicide myth can provide resources for readers who are in or know of someone who is in a potential crisis. The CDC, the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) offer valuable information. The U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 800-273-TALK (8255).

Recommendations developed by journalism and suicide-prevention groups with the Annenberg Public Policy Center (http://www.reportingonsuicide.org) note that reporters should consult reliable sources on suicide rates, such as those produced by the CDC, and provide information about resources that can be helpful to people in need.

Methodology

News and feature stories linking suicide with the holidays were identified through the Nexis database, with “suicide” and “Thanksgiving/Christmas/New Years” or “holidays” as search terms from November 15, 2017, through January 31, 2018. Researchers determined whether the stories supported the link, debunked it, or showed a coincidental link. Only domestic suicides were counted; overseas suicide bombings, for example, were excluded. Thanks go to Ilana Weitz, who collected and supervised the coding of the stories; Sebastián Lemus Camacho and Olivia Bridges for assistance in coding; and Emily Maroni for assistance in charting the data. Thanks also go to Alex Crosby and colleagues at the CDC for providing monthly rates of suicide in the United States.

Coverage of this research includes:

- Behind the spring suicide peak (The Wall Street Journal, April 19, 2019)

- Suicide rates rise in the spring. Here’s what you need to know (The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 29, 2019)

- Letters: Article was wrong about December suicide spike (The Daily News (Texas), December 28, 2018)

- Fact Check: Media may unintentionally mislead about holiday suicide statistics (88.5 WFDD, December 27, 2018)

- Tips on how to beat back ‘Holiday Blues’ (Times Virginian, December 26, 2018)

- VERIFY: No, the suicide rate does not spike during the holiday season (WUSA9, December 24, 2018)

- Suicide numbers continue to climb, though some push back on holiday-suicide ‘myth’ (The St. Augustine Record, December 22, 2018)

- Are there really more suicides at Christmas? (Wired.it, December 22, 2018)

- Holiday blues? Here are support hotlines, resources (WLWT5, December 21, 2018)

- Why the myth that suicides increase during the holidays is dangerous (Newsy, December 21, 2018)

- Blue Christmas: It’s the most wonderful time of the year — but what if it’s not for you? (USA Today, December 17, 2018)

- Journalists perpetuate myth about suicide during winter holidays (Journalist’s Resource, December 14, 2018)

- ‘Holiday spike’ in suicides is a myth: UPenn study (Metro USA, December 13, 2018)

- The media’s holiday suicide myth will never die (The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 13, 2018)