Last updated March 17, 2022. This page will be updated as our understanding of COVID-19 increases.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Since then, millions of people have been infected or died of the virus. At the same time, there has been a pandemic of misinformation and false claims regarding the disease and its origin, transmission, virulence, prevention and treatments. Below is a guide for understanding how to protect yourself and your community. Visit SciCheck, a project of FactCheck.org, to learn more.

Getting COVID-19 is Risky

- As of mid-September, more than 1 million Americans – or 1 in 319 people — have died of COVID-19 since the pandemic began.

- COVID-19 can be dangerous to everyone, but especially for people who are older, pregnant or have certain health conditions.

- Children are less likely than adults to get very sick. But some kids have been hospitalized, developed a rare but serious complication known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), or have died.

- Although most people with COVID-19 get better within weeks, some experience ongoing health problems, also known as “long COVID.”

COVID-19 is riskier for those who are pregnant

- Due to changes in the body during and after pregnancy, being pregnant or recently pregnant increases the risk of developing a severe case of COVID-19.

- Getting COVID-19 while pregnant raises the chance of an early birth (delivering before 37 weeks) and stillbirth.

There is no cure for COVID-19

- There are a few COVID-19 treatments for people who are hospitalized or high-risk, but there is no cure for the disease.

- Two antiviral pills have been authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for high-risk patients. The pills need to be taken starting no later than five days after symptoms begin.

- Another antiviral, remdesivir, may help hospitalized or high-risk patients. It must be given through an IV.

- Several monoclonal antibody drugs have been authorized for high-risk patients, although not all work against all variants.

- Studies have found that hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin don’t work to treat COVID-19.

COVID-19 vaccination is beneficial

- Vaccination greatly reduces the chance that you will become very sick or die from COVID-19.

- Booster shots increase protection.

- Studies suggest vaccination also prevents new or ongoing symptoms of COVID-19 after an infection, or what is known as “long COVID.”

- It’s a good idea to get vaccinated even if you’ve already had COVID-19 because the vaccine will increase your protection.

Vaccines do work against Omicron

- The vaccines are not very good at preventing infection with the omicron variant and its subvariants, unlike with past variants. But they still provide protection against severe disease.

- Booster shots increase protection against hospitalization and death — and for a short period of time, reduce the risk of infection.

It’s better to get immunity from a vaccine than from an infection

- It’s true that natural immunity can provide protection, but that requires infection and the risk of getting sick. A small proportion of people who had infections may not develop much immunity.

- Studies show the vaccines give an immunity boost to those who were previously infected.

The vaccines are safe

- More than half a billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have now been administered in the U.S.

- The vast majority of people experience only short-term side effects such as a sore arm, tiredness or a headache — or no side effects at all. These side effects aren’t dangerous and are a sign that the vaccine is working.

- Serious side effects are rare. For instance, there have been about 5 cases of anaphylaxis, a serious allergic reaction, per 1 million vaccine doses administered. Vaccination sites can immediately treat this reaction.

- Another rare side effect is inflammation of the heart or surrounding tissue, mainly seen in younger males soon after a second dose of an mRNA vaccine. Data show that this risk is very low and that most people respond well to rest and treatment.

- These serious side effects are so rare that they weren’t detected in the clinical trials, which included tens of thousands of participants, and were published in the peer-reviewed New England Journal of Medicine.

- Safety monitoring continues to show the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks. Getting COVID-19 is far riskier than getting vaccinated.

Data show the vaccine is safe before, during and after pregnancy:

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the CDC all recommend that pregnant and breastfeeding people get vaccinated.

- Numerous studies and safety monitoring data from thousands of vaccinated pregnant people show that vaccination is safe for pregnant people. Scientists haven’t found an increased risk of miscarriage or of other bad outcomes for the mother or baby following vaccination.

- Vaccination during pregnancy also may protect babies, as potentially protective antibodies have been found in umbilical cord blood and breast milk of vaccinated mothers.

- A CDC study found that two doses of the mRNA vaccine during pregnancy reduced the risk of COVID-19 hospitalization in infants younger than six months old.

- There is no evidence the vaccines cause fertility problems, in either women or men.

- COVID-19 vaccination may slightly lengthen a menstrual cycle, but the effect is temporary. And there’s no indication it’s harmful.

COVID-19 vaccination in children

- For the initial shots, kids 12 and up can receive the adult Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna vaccines. Smaller-dosed pediatric versions are authorized for children as young as 6 months old.

- As with adults, children may have temporary side effects, but serious side effects are rare.

Vaccines have been preventing disease for more than 100 years

Smallpox, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, whooping cough, chickenpox and diphtheria can all be prevented thanks to vaccination.

Before they are authorized, vaccines go through many forms of independent scientific review

The CDC and FDA continue to monitor the safety of vaccines after they are authorized

Other precautions are still important

- Masking, physical distancing and good ventilation are still important when indoors and near others to help prevent transmission of the virus.

- Fully vaccinated and boosted people, even those showing no symptoms, can still spread the virus to others.

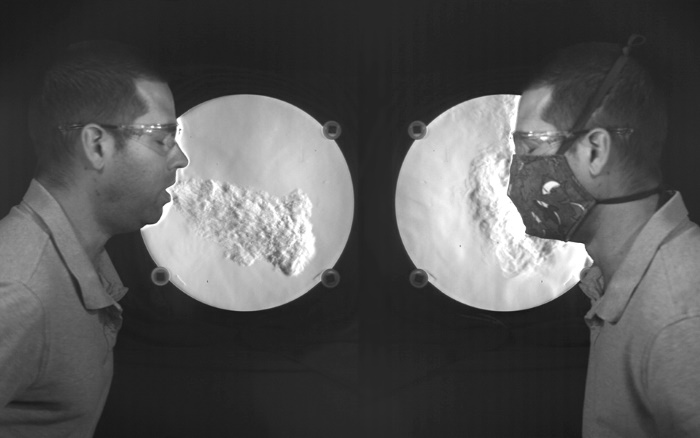

- Wearing a high-quality, well-fitted mask reduces your chances of getting or spreading the coronavirus. Surgical masks and KN95s are better than cloth masks. N95s are best.

- Get tested if you have symptoms, were around someone with COVID-19, and before attending a gathering.

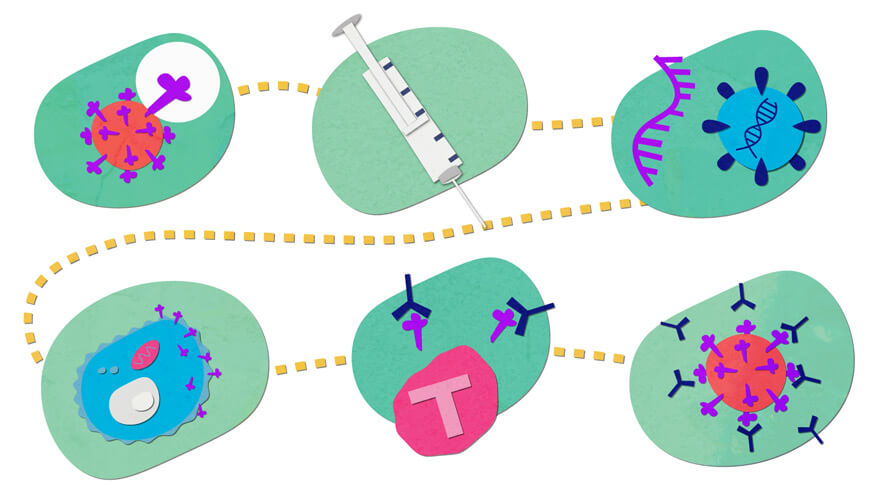

How these vaccines work

The vaccines trigger an immune response against the coronavirus’s spike protein, which sits on the surface of the virus and is what it uses to enter cells.

Most of the vaccines deliver instructions to cells to produce a harmless protein, similar to the coronavirus’s spike protein – except the Novavax vaccine, which itself contains the spike proteins.

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines deliver these instructions using modified messenger RNA, or mRNA. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine uses a modified, harmless adenovirus.

When cells read the instructions, they make the harmless protein.

That triggers the immune system, generating protective antibodies and activating other immune cells known as T cells.

If you are later exposed to the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, your immune system can recognize it and protect you.

The vaccines don’t alter a person’s DNA. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines don’t enter the nucleus of a cell, where DNA is. The J&J vaccine doesn’t integrate into human DNA.