Motor vehicle crashes are a leading cause of death and injury for U.S. teens, and driver error is one of the main reasons for those crashes. Young driver training before granting them licenses can help lower crash rates, but according to a new paper, many U.S. states do not require sufficient preparation before allowing these drivers on the road.

In “Variation in Young Driver Training Requirements by State,” published on June 17 in JAMA Network Open, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia cataloged each U.S. state’s requirements for licensure.

The major policy in the United States directed toward adolescent drivers is Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL), which places restrictions on drivers (time of day, and number of passengers) and delays full licensure. These rules help reduce teen crashes, but those crashes remain high and are the greatest source of injury for this age group. Crashes also decline as adolescents gain more driving experience, suggesting that teens’ skills are not fully developed at licensure.

“A lot of adolescents are allowed to drive without sufficient training before they get their provisional license,” says co-author Dan Romer, research director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC).

In addition to GDL, some states require young driver training in the form of adult-supervised practice hours (ASP), often with a parent or guardian, and/or professional behind-the-wheel training (BTW).

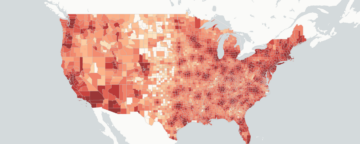

The researchers found that a majority of states (29) require both BTW and ASP training. However, 16 states, including Pennsylvania, had no BTW requirements, relying only on ASP, and the evidence for ASP’s safety benefits is not strong. Plus, seven of those states had no ASP requirement either for those older than 15.

Professional BTW training has greater potential to reduce crashes, but requiring it has drawbacks as well.

“The challenge is that some people can’t afford to pay for behind-the-wheel training, so they wait to get their license at age 18 when they have aged out of the requirement, or possibly drive without a license,” says lead author Elizabeth Walshe of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP).

Online training programs, the authors write, “could be a strategy to increase access to training and reduce disparities in licensure and crashes.” More testing of this approach is needed, however.

Meanwhile, “clinicians should be aware that although their patients may be licensed, they may be ill-prepared for safe driving,” the authors write. “Clinicians should generally advise parents to go beyond state minimum requirements as needed for their child.”

“Here at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, we now offer a virtual driving assessment to teen patients, right in their primary care clinic, so that they can test their skills safely, get personalized feedback on how they did, and continue to hone their safe driving skills on the road,” Walshe says.

In addition to Romer and Walshe, a research scientist with the Center for Injury Research and Prevention (CIRP) at CHOP, the research team includes CIRP director and APPC distinguished research fellow Flaura K. Winston, and Nina Aagaard of the CIRP.

“Variation in Young Driver Training Requirements by State,” was published in JAMA Network Open on June 17. DOI: .

The research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD108249). The research team acknowledges a generous gift from and partnership with NJM Insurance Group, which supports our ability to administer a virtual driving assessment as part of routine adolescent care in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, two states without mandatory behind-the-wheel driver training before licensure.