The Annenberg Debate Reform Working Group (for biographies of members see Appendix One) was created by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania to explore ways to increase the value and viewership of presidential general election debates, taking into account the ways in which the rise of early voting, the advent of social media, establishment of new media networks, changes in campaign finance, and the increase in the number of independent voters have altered the electoral environment. It would be difficult to overstate the significance of these changes.

- When general election presidential debates emerged in 1960, network television dominated the media landscape. In an era where 90% of television viewers watched three networks, and had few other choices, the “roadblocked” debates commanded the available air space.

- When the Republican and Democratic political parties formed the Commission on Presidential Debates in 1988 (for a history of debate sponsorship see Appendix Two), there was no Internet or vote by mail, and “early” voting was primarily absentee balloting with significant restrictions.

- In 1988, there was no Fox News, no MSNBC, no Univision or money spent by the campaigns on cable advertising (and no digital on which to spend).

- In 1988, there were no Super PACs and by today’s standards the levels of campaign-related “issue advertising” and “independent expenditures” were small. In a number of past decades, campaign acceptance of federal financing imposed limits on spending.

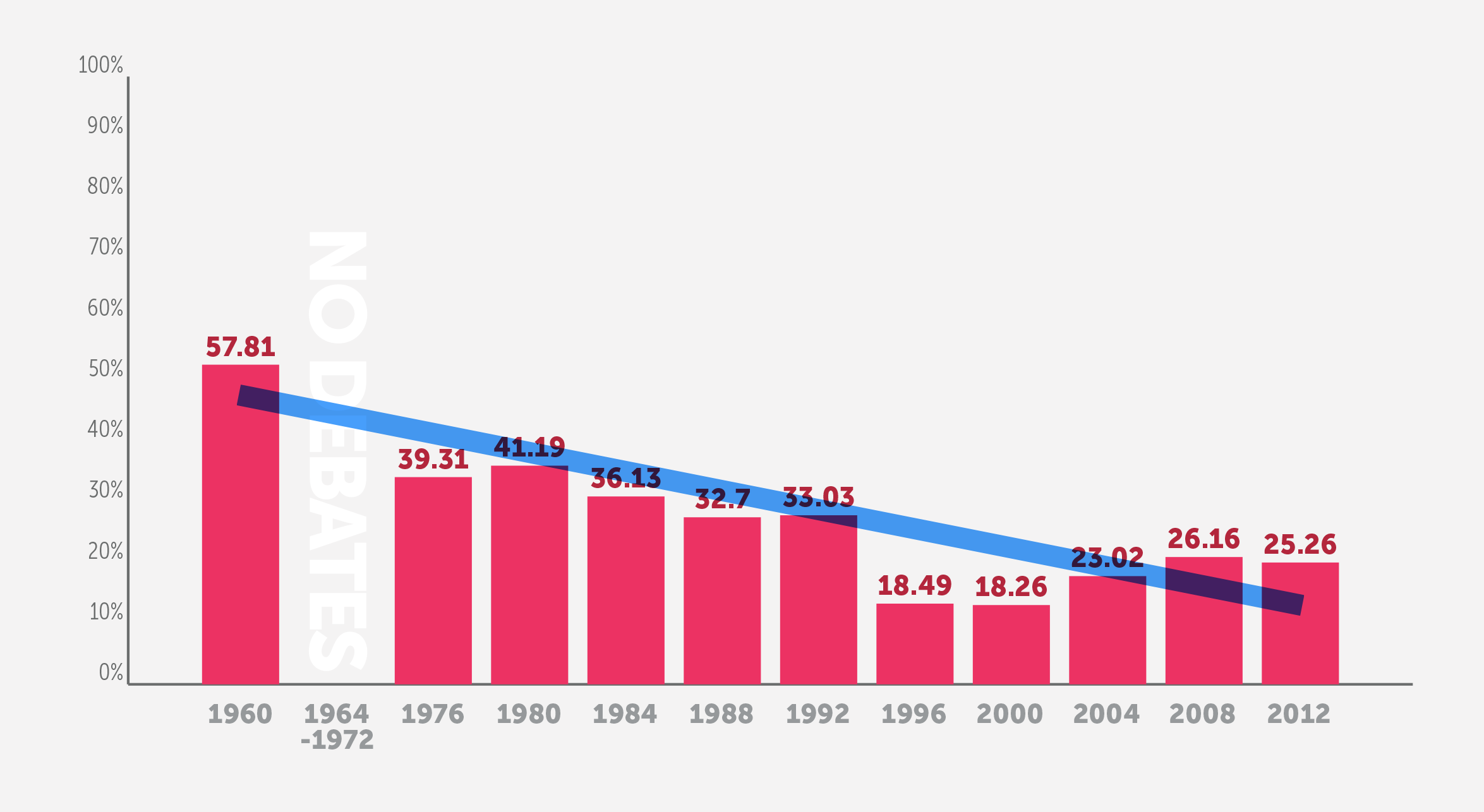

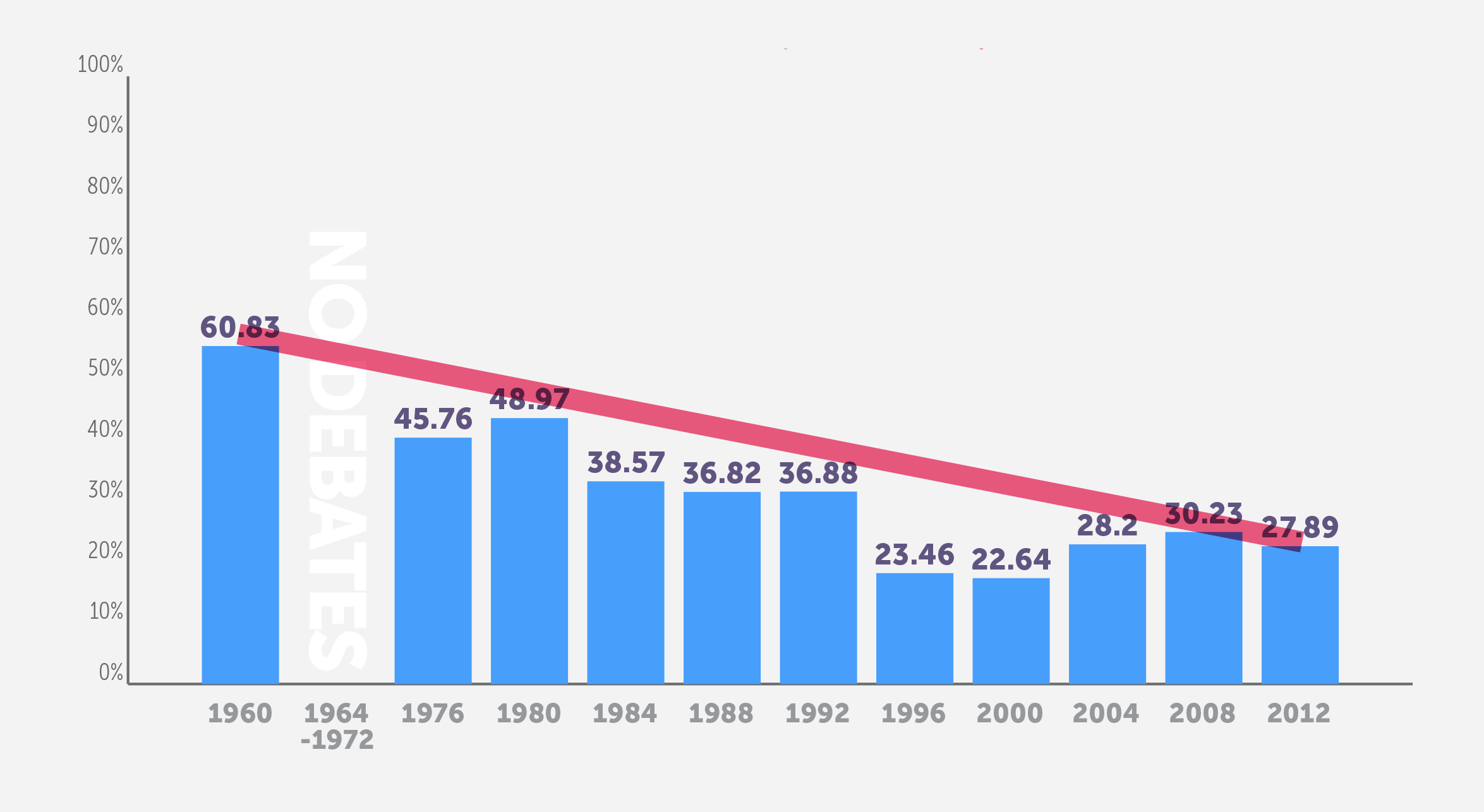

Since 1960, transformational shifts in television viewing – the plethora of cable channels, Internet streaming, and other methods of viewing video content – have dramatically eroded the power of the “roadblock.” Nielsen data show that the percent of U.S. TV households viewing the debates has declined from 60% in 1960 to about 38% in 2012. Additionally Hispanic media now attract substantial audiences. In both the July sweeps of 2013 and 2014, the number one network among both those 18-49 and those 18-34 was Univision.

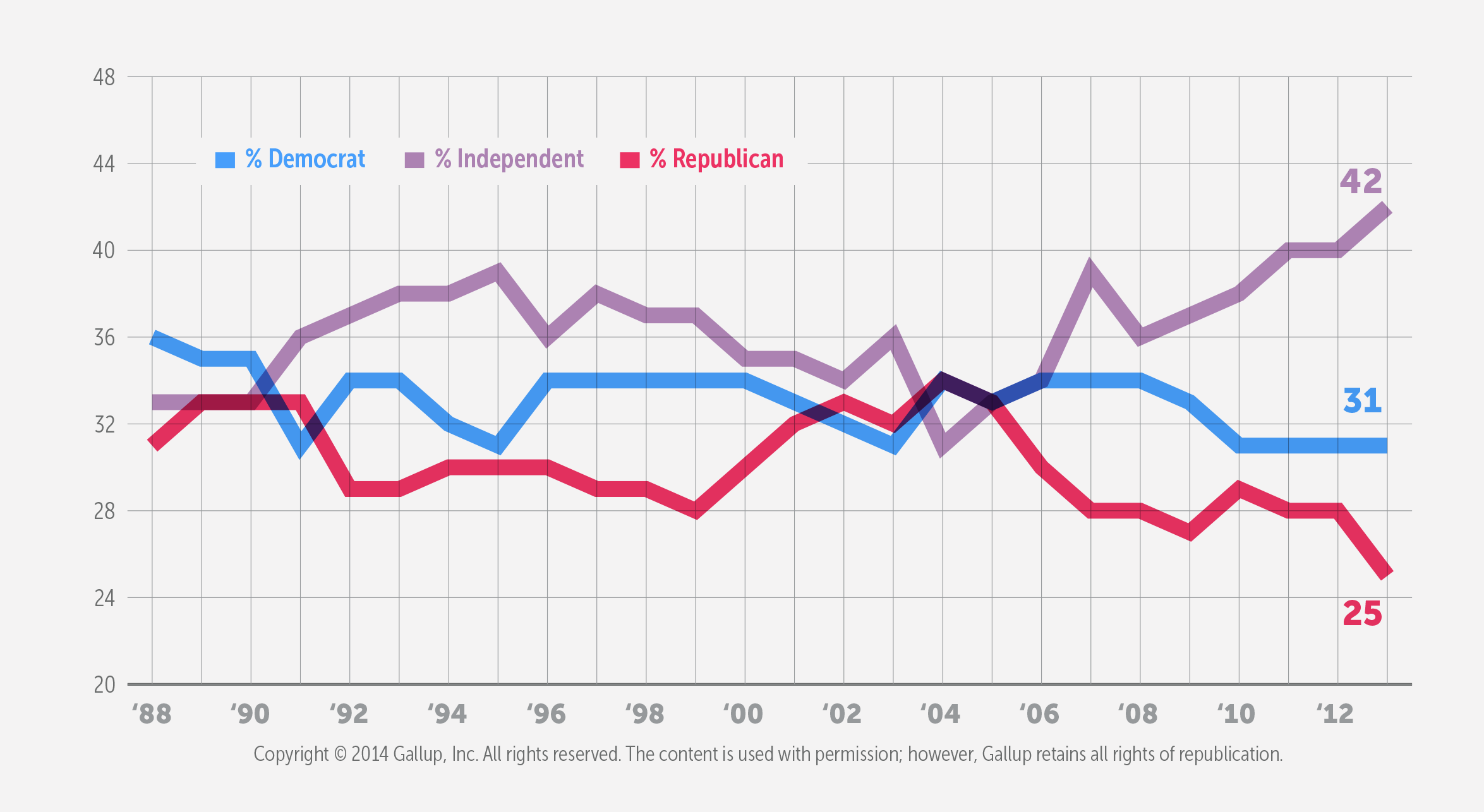

In today’s environment, traditional media are working to adapt to a world in which digital content is increasingly a primary source of “news” for many Americans. Moreover, the fastest-growing block of voters in the country considers itself non-aligned and not represented by the major political parties who originally formed the Commission on Presidential Debates. The new “news” is often delivered in 140 characters, and a voter’s most trusted information source is often a “friend” from Facebook. Voting is conducted earlier and earlier, by mail and in-person. Super PACs and other funding organizations play an increasing role.

Those who organize debates and those who participate in and watch them generally share the view that overall: these exchanges should be informative and not “canned”; the topics should be wide-ranging and relevant to voter choice and interest; and the vice-presidential as well as the presidential candidates should be heard. The Working Group agrees. But while in recent campaigns the debate process has incorporated more open formats, and moved from the traditional timed answers and strict structures, in general it has changed very little since 1992, when the single moderator and town hall formats were adopted. Very few “television programs” have succeeded with a format that is more than two decades old.

Yet, these quadrennial events remain important. Not only do they continue to attract a larger viewing audience than any other campaign event or message, but also, consistent with past data, a 2014 survey conducted by Peter D. Hart and TargetPoint Consulting for the Working Group found that “Presidential Debates” were a top source of information in helping voters with their decisions and deemed the “most helpful” by a plurality of respondents. However, the proportion viewing debates is not as large as it once was or as it could or should be. Although Nielsen data reveal that the numbers viewing broadcast and cable debates have increased in every election year since 1996, the proportion viewing debates on TV and cable is down from the 1992 level. Importantly, a Nielsen study commissioned by the Annenberg Public Policy Center reveals that although viewership numbers have increased somewhat since 1996, the largest growth is among those aged 50-64, a cohort socialized in an earlier media era.

At the same time, substantial numbers fail to watch an entire debate or multiple ones. Across the 2004-2012 election years, a plurality of debate viewers watched only a single debate (See also Appendix Three). In particular Nielsen analysis confirms that:

In 2012, 20.2% of viewers 18 or older watched at least some of one debate, 16.2% watched at least some of two debates, 15.3% watched at least some of three debates and 14.9% watched at least some of all four debates. Across all debates, those who viewed at least some of one averaged 35.1 minutes of viewing time, those who watched at least some of two averaged 47.8 minutes, those who viewed at least some of three averaged 66.1 minutes and those who viewed at least some of four averaged 172.5 minutes of viewing time.

There is no question that debates have a unique capacity to generate interest in the campaign, help voters understand their choices in the upcoming election, forecast governance, and increase the likelihood that voters will cast a vote for the preferred candidate rather than primarily because of opposition to the opponent. With needed reforms, presidential general election debates can do a better job of meeting these goals and can also increase the level and amount of viewership; without change, the proportions viewing debates may decline further and the levels of viewership among two important constituencies – the young and Hispanics – stagnate.

The Goal of Reform: Democratizing the Debate Process

Reform of the presidential debates should be accomplished by re-shaping formats, emphasizing candidate accountability, better aligning debates with the changing attitudes of the electorate, and modifying the debate process and timing.

Overall, the effect of the desired changes is a democratization of the debate process. To this end, and as discussed at length in this Report, the Working Group recommends:

Expanding and Enriching Debate Content

- Increase direct candidate exchanges and otherwise enhance the capacity of candidates to engage each other and communicate views and positions;

- Reduce candidate “gaming” of time-limited answers and create opportunities to clarify an exchange or respond to an attack;

- Enlarge the pool of potential moderators to include print journalists, university presidents, retired judges and other experts.

- Use alternate formats for some of the debates, including a chess clock model that gives each candidate an equal amount of time to draw upon.

- Expand the role of diverse media outlets and the public in submitting questions for the debates; and

- Increase the representativeness of audiences and questioners at town hall debates.

Broadening the Accessibility of the Debates

- Embrace social media platforms, which are the primary source of political information for a growing number of Americans, and facilitate creative use of debate content by social media platforms as well as by major networks such as Univision, Telemundo, and BET, by providing unimpeded access to an unedited feed from each of the cameras and a role in framing topics and questions; and

- Revise the debate timetable to take into account the rise of early voting.

Improving the Transparency and Accountability of the Debate Process

- Eliminate on-site audiences for debates other than the town hall and, in the process, reduce the need for major financial sponsors and audiences filled with donors;

- Publicly release the Memorandum of Understanding governing the debates as soon as it is signed;

- Require the moderators to be signatories to the MOU to ensure compliance with the agreements about rules and formats; and

- Clearly articulate the standards required of polls used to determine eligibility for the debates.

Expanding and Enriching Debate Content

The proportion of the electorate viewing debates is substantially lower than it once was (see also Appendix Four).

Moreover, debates are not giving voters as substantive an understanding of the candidates as they might. Candidates and their party representatives view them as a hybrid of Sunday morning interviews and gladiatorial clashes, and express frustration with the constraints the joint press conference structure imposes on their ability to communicate their positions, priorities and core political messages, and clarify distinctions between or among the candidates.

The Working Group believes that debate formatting needs to be rethought. There are several contributing reasons. Across the past half century of scholarship on debates, scholars have noted how format limitations “have made it difficult for audiences to see the ‘real substance’ of the candidates’ positions and policies”. These same formatting conventions “not only thwart sustained discussion of serious issues, but also encourage one-liners and canned mini-speeches”.

Looking back at the 1960 debates is a striking exercise that offers a model for considering reforms in the current structure for the Working Group. With eight-minute opening statements and longer answer times, both personalities and positions were clearer and more compelling. The highly moderated format we have today has produced shorter answers, but the result has been less substance and more equivocation. At the same time, strict time allotments treat all questions as equally important and encourage candidates to use all of the allocated time as well: if the candidates try to respond at greater length, they appear to “filibuster;” if they abbreviate their responses, they convey lack of interest or knowledge. In any case, the short-answer format rewards those who resort to clever quips and sound bites.

Because it believes that the general format has calcified over 52 years, and especially the past 20 years, when innovation has largely stopped, the Working Group has adopted two fundamental goals for evaluating alternatives: (1) The voters should learn more about who the candidates are, what they stand for and what they would do in office, and (2) The candidates themselves should be responsible – and therefore accountable – for the quality of their performance. With a candidate-centric format, success or failure rests on the individual candidates’ shoulders.

Rethinking Formats for Debates

Many of the Working Group’s recommended format changes have been proposed before. In one major study, respondents who had participated in “Debate Watch,” a voter education program involving tens of thousands that was originally associated with the Commission on Presidential Debates, favored “something closer to a Lincoln-Douglas debate with less intrusion from the moderator. This would include cross-examination by the candidates, opening and closing statements…a limited number of topics per debate, different topics in each debate, more flexible time limits that would allow for more depth of analysis and clearer comparisons and contrasts between or among positions while avoiding discussion of a topic from a previous question during a subsequent topic, rules that allow the moderator to keep the candidates on the topic…” That work noted as well that “many participants expressed a belief that cross-examination would improve the debates by making candidates more spontaneous and by providing viewers with better information and bases for comparison. One of the major criticisms of the existing formats was that they did not produce enough interaction between the candidates…” Because the Annenberg Working Group agrees with many of these sentiments, its members recommend retention of the town hall, the addition of two new formats—the chess clock model and the reformed standard model—and a re-evaluation of the roles of the press and moderator.

Alternative Formats

At the core of the Working Group chess clock format is an idea that has been circulating for more than two decades. The seventh recommendation of the 1986 Institute of Politics-Twentieth Century Fund Report also known as the Minow report (see Appendix Two) read: “The use of journalists as questioners should be eliminated in favor of allowing the candidates the opportunity of questioning each other.”

The “Chess Clock” Model. Under this model, each candidate is allotted approximately 45 minutes of speaking time. Eight topics with equal blocks of time are provided. Anytime a candidate is speaking, that candidate’s clock visibly counts down. To take control of the floor, a candidate simply hits the chess clock. No answer, rebuttal or question may exceed three minutes. The hard time stops are agreed upon; when a candidate runs out of total time, he or she has exhausted the right to speak. Remaining time at the end of the moderator-posed topics can be used for a closing statement.

In the chess clock model, the candidates, not the moderators, would be responsible for follow-up. As discussed below, reform of the standard model would have the moderator enforce time limits and raise topics culled from a variety of sources. The moderators would not be tasked with asking follow-up questions; instead, candidates would be expected to challenge incomplete and nonresponsive statements by the opposing side.

The topics would be drawn from a pool of submissions from broadcast, print and social media, and from the general public, vetted by an editorial committee formed perhaps of representatives of leaders of the presidential libraries, presidents of major public and private universities, or the heads of major public libraries. The selection filter is the question, “What will a President face while in office – and how is he or she likely to respond?”

Under this model, candidates can choose to go into greater detail on matters of greater importance to them; they are not compelled to pad time on others.

The Reformed Standard Model. Under the reformed standard model, there would be no chess clock and the time would be allocated between the candidates on the more traditional understanding: e.g., one minute for response, 30 seconds for rebuttal. The changes would otherwise remain the same as in the chess clock model in two respects: the role of the moderator and the source of the questions. Two additional features, giving candidates more flexibility to rebut or clarify and the opportunity to prepare statements on some topics in advance, would be added to increase their opportunity to engage the opponent and feature central points of their agendas.

This first, which involves allocating to each candidate two “points of personal privilege” in congressional terms, or “challenge flags,” allows each candidate to exercise two 90-second opportunities to deviate from the format and make a statement. This allows each to clarify a previous response or respond to an attack when the formal format would by rule (if enforced) preclude it.

The second additional feature would call for each candidate to be given two different topics ahead of time. Each may prepare a four-minute response; the other candidate, also supplied with the topics in advance, has equivalent time to offer a counterstatement, rebut, and cross-question the first candidate. Alternatively, in advance of one of the debates, each candidate would select two topics with two additional ones decided by the moderator through the reformed process recommended in this Report, and two by some form of social media ballot.

Town Hall Debates

The town hall format is an important feature of presidential debates. Although the first presidential debate of 2012 drew the largest number of viewers, the town hall “had a higher rating and held viewers’ attention longer.” The town hall would follow roughly the same format as used in recent years, but with, again, the adjustment in the role of the moderator, who would enforce process requirements and time limits, but would not have a role in asking follow-up questions or supplement the roster of questions posted by the citizen-participants. The town hall debate should include no live audience other than the citizens who are the participants in the town hall, and who ask the questions. The questioners should be selected from undecided voters in battleground states and not, as has occasionally been the case in the past, from communities in less competitive jurisdictions that do not offer the same desirable diversity of views. The set should be designed to minimize the physical “traffic” both between the candidates and between the questioners and the candidates, allowing for an orderly and clear progression of debate exchanges.

Re-evaluating the Role of the Press and Moderators

At the request of the Annenberg Working Group, in March 2014, Peter Hart convened five focus groups in Denver involving individuals who voted in 2012 and reported having watched some or all of one or more 2012 presidential general election debates. “The single largest criticism of the debates centers on the inability of moderators to do their job,” concluded Hart. “Some participants perceive some moderators to be biased and ruining the fairness of the debate. Others complain that the moderators either do not have the skills to control the candidates or to call them on ‘non-answers.’”

| 18-34 (A) | 35-49 (B) | 50-64 (C) | 65 + (D) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The moderators tend to play favorites, giving one of the candidates the edge | 32%BCD | 43%A | 44%A | 44%A | 41% |

| The moderators tend to lose control of the debate and the candidates interrupt one another and go over the time limits | 29%D | 27%CD | 36%B | 42%AB | 33% |

| The moderators overstep their boundaries and inject themselves in the debate process | 23%CD | 32% | 33%A | 35%A | 30% |

| The questions moderators pose are not the right questions on the important issues | 26% | 27% | 30% | 33% | 29% |

The national survey conducted for the Working Group by Hart reinforces concerns about the role of the moderator.

The Working Group raised an additional set of concerns. In recent years, the moderator has been a television journalist, and more often than not a current or former anchor of a major network news program. When a network uses a debate as an opportunity to showcase its broadcasting talent and enhance its brand, the somewhat arbitrary selection of moderators from a maximum of four networks in a world now populated by many more than that creates a competitive advantage for the selected outlet. One result of all of this is that the debates can take on the appearance of marketing opportunities for the network whose reporter or anchor is moderating. Moreover there is pressure on the campaigns to push for or accept certain moderators for debates. Also of concern is the fact that moderator selection is not a transparent process.

The format changes recommended by this group would address many of these concerns by focusing the role of the moderator on moderating.

A review of press coverage surrounding the 2012 general election confirms that the moderators – their performance, the reactions to their performances, perceived tilts toward one candidate or another – have become an integral part of the presidential debate story. This attention to the role of the moderator stems in part from two aspects of the role which raise the question of whether these debates are best moderated by individuals in their role as journalists or, moderated by an individual whose sole responsibility is ensuring that the debate process works well. The Working Group favors the latter. The criticisms of debate formats as joint news conferences or joint Sunday show-type interviews reveal the inherent tension in the role of journalists acting in their capacity as journalists while also performing as moderators.

At present, in the debates other than the town hall, the moderator decides which questions are asked, or which topic areas are covered, with as much or as little input from the public or other journalists as he or she wishes. This can result in questions that advance the news agenda more than public understanding of the candidates, their plans and position on issues. Press control of content and pursuit of “follow-up” can create an interview or Sunday show dynamic in which the candidate is engaged with the moderator, as opposed to the other candidate. Candidates end up preparing to debate the moderator as well as their opponent(s).

Consistent with our belief that the debates should be a forum for the views of, and exchanges between, candidates, the Working Group recommends the following areas for reform:

Development of Questions: The debates should employ a more formal process of soliciting topics and questions both from the general public through a variety of platforms as well as from a broad group of knowledgeable experts that would include print as well as broadcast journalists. The questions could be curated by a group, potentially made up of directors or members of boards of presidential libraries and major public libraries, or public and private university presidents, with the moderator responsible for framing the questions. This reform would invite greater diversity, and give both the public and a broader representation of the press corps an opportunity to identify topics and questions that the debate should cover.

We believe that a full third of the questions by the moderator in the debate should be obtained from non-news sources. On an individual level, this change gives voters and politically interested Americans greater opportunity to shape the debates. Involving the audience, however, demands participation that enhances the debate viewing experience. Audience participation should be much more than a novelty – it should contribute to the greater dialogue and provide a meaningful way to participate. Moreover, audience participation has the potential to help direct conversation and reaction before and after the debate and in the process increase interest. If well structured, a high level of interaction between the public and the people running for president furthers our goal of helping Americans make the most informed choices.

Expanding Pool of Potential Moderators: Television networks argue that live, televised events can be effectively moderated only by experienced broadcast journalists. The challenge of moderating the debate, with the producer giving guidance in the moderator’s ear, is real – trying to make sure time is allocated fairly, that the order of responses is correct, and that the candidates’ focus shifts as needed to different topic areas. Moreover, there is a belief that journalists offer an informed perspective that ensures that important topics are covered and candidates answer the questions asked.

However, as noted, a moderator’s control of content and pursuit of “follow-up” can create an interview or Sunday show dynamic in which the candidate is engaged with the moderator, as opposed to the other candidate.

With a more limited role for the moderator, there is no reason that the potential moderator pool could not be broadened to once again include print journalists as well as other persons of stature such as university presidents, retired judges, historians, and others with demonstrated credibility– as was proposed at the birth of the televised debates in 1960. This also would address the diversity issue. In the past, debate moderators have not reflected the diverse makeup of the country.

Adopting a More Inclusive, Transparent Selection Process: The current process of choosing moderators is not transparent. We recommend that a designated group, again potentially made up of presidential library heads and board members, develop an initial list and that the campaigns select a moderator from that list. While the system may produce one moderator who would facilitate more than one debate, we would strongly suggest using different moderators for different debates to add variety and increase public interest.

The Question of the Criteria for the Inclusion of Minor Party or Independent Candidates

Over the course of the presidential debates, there has been limited independent or minor party candidate participation. In 1980, independent candidate John Anderson was included in the first debate (although Democratic nominee and incumbent President Jimmy Carter declined to participate). In 1992, independent candidate Ross Perot participated in all of the presidential debates, but was not invited to the debates four years later. Those are exceptions to the general pattern that presidential debates feature only the two major party candidates.

The Commission on Presidential Debates administers a two-part test for inclusion of candidates: (1) Any candidate included must have the ability to be elected in the general election by qualifying for ballot inclusion in states adding up to at least 270 electoral votes, and (2) Any candidate who passed the ballot test must reach at least 15% in independent national surveys in the period leading up to the debates.

Whether they identify themselves as independents or non-aligned or just refuse to state a preference, one of the significant changes in American elections since the Democratic and Republican parties formed the Commission in 1987 is the growth of those who call themselves non-aligned voters in this country.

As important is the fact that 50% of those in the millennial generation, now ranging in ages from 18-33, described themselves as political independents in March 2014.

Given this reality, and the fact that the independent/non-aligned candidates have succeeded in winning statewide races over the past decade, the Working Group discussed whether the time has come to revisit the standard for including candidates. It heard views on this topic from advocates of liberalized standards for the inclusion of independent candidates, including from those arguing for a guaranteed invitation for at least one independent candidate regardless of the person’s standing in the polls and electoral viability. It has been argued that the rules should take account of the possibility that through inclusion in the debates an independent candidate could build the potential for victory that he or she did not have at the outset.

There is support in both the focus groups and in the survey for a lower entry threshold. Where 41 percent of those surveyed favor the status quo, 47 percent oppose limiting “the debates to the two major party candidates unless a third-party candidate can exceed 15% in the polls.” The survey asked which of two statements came closer to the respondent’s view:

Statement A: The rules for a third-party candidate inclusion should be relaxed so that it is easier for them to be part of the debate. Even if it is unlikely that they will win the presidency, it would make the major candidates respond to their ideas.

Statement B: The rules for a third-party candidate inclusion should not be changed, because the third-party candidates take away from the central purpose of listening to and watching the two people who are most likely to become the president.

In response, 56 percent said the rules should be relaxed while 28 percent said they should not be changed. Fifteen percent offered no opinion or did not know. Similarly, respondents in Hart’s focus groups favored “making it easier to allow third-party candidates in on the debates.”

In discussing alternatives for the American election, the Working Group examined the current 15% threshold for inclusion, measured by public opinion polling, coupled with qualification for the ballot in enough states to win a majority of the Electoral College. It considered the balance to be struck between ensuring a diversity of views, and giving voters the opportunity to consider the views of the candidates—the major party candidates—with the highest likelihood of being elected. On this question, there was not a consensus on the best solution.

The Working Group concluded that the debate must remain principally an exchange of views for the benefit of voters who are faced with a choice of a potential president, and that therefore the debaters should have by a fair measure a realistic chance of winning the election. But the Group could not arrive at a consensus and has not therefore made a recommendation for a modified standard.

However, a majority of the Working Group agreed that the selection criteria now in place should be replaced with a structure that, in addition to demonstrated capacity to win a majority of electoral votes, would involve; a) lowering the threshold for the first presidential debate to 10%, b) raising it to 15% for the second; and then c) increasing it to 25% for the third and final debate. This process would facilitate inclusion of third-party or independent voices at the outset of the debate schedule, while requiring a showing of expanded support as the campaign—and debate period—continues. These proposed changes respond to the argument that independent candidates have to clear too high a hurdle in the first instance, and if given a greater chance at the outset to participate, may be able to build support.

Because standing in polls plays a critical role in determining eligibility for debate participation, the Working Group does believe that it is important that the standards required of polls used to determine eligibility are clear; the number and identity of the polls on which the decision will rely are announced in advance; the survey question that will be used to assess eligibility is disclosed in advance; and answers are provided in advance to such questions as: What happens if a candidate falls below the polled threshold but is nonetheless within the margin of error?

Broadening the Accessibility of the Debates

The Internet has produced increased democratization in the political process. Almost overnight, information became available from a variety of sources, not just the major networks, and opened a platform to the average person for voicing opinions and sharing news and coverage.

Debates have failed to keep up with the evolving digital viewing habits of the American public. At the same time, social media have altered the ways in which the public consumes the debates. The May 2014 survey conducted by Hart found that “When young people do watch debates, they are significantly more likely to actively follow the debate through social media platforms, such as Twitter or Facebook. More than a quarter (28%) of 18-34 year olds and about a fifth (19%) of 35-49 year olds said they both watched and actively followed the 2012 debates on social media platforms. Significantly fewer older adults reported such activity (12% 50-64 year olds and 8% of 65 and older).” Broadcast and cable networks play an essential role, but the shifting media habits of the American electorate – characterized by the expanding number of cord-cutters and off-the-grid segments – are noteworthy, and by 2016, the shift to digital media consumption will be even more pronounced.

We would recommend embracing this changing media landscape by providing full access to debate content on a flat, universal feed developed according to predefined, public technical standards and shared with media companies and individuals alike. We would also complement a common feed with clean, succinct, accessible data and analytics. In the Hart survey, 55% of the public surveyed and 69% of those 18-34 support streaming debates over the Internet on external outlets simultaneously as the debate is going on. Doing so frees campaigns and media providers to focus on what matters: creating valuable debate experiences for the voters.

To facilitate these changes, technological infrastructure should provide a level playing field for competition and innovation. Universal access is ideal for this purpose. Flexible and adaptable, this foundation will allow the market to develop media delivery models and offerings that suit viewers of different ages and habits.

Digital content providers deserve a central role in setting these universal requirements. Even though we don’t know what those will look like in 2016, let alone 2020 or 2024, if debates are to stay relevant, they must adapt to the variety of viewing habits and technologies in use.

An election comes down to the millions of individual decisions made by voters. The voters—not broadcasters, media providers, or networks—ought to determine how, where, and when debate content is used. Open, universal access to debates, with meaningful content presented in a relevant way, can help ensure the continuing viability of the presidential debates well into the future.

Revising the debate timetable to take into account the changes in voting behavior since 1988, particularly early voting. Because the fall calendar of an election year includes the Summer Olympics, Major League Baseball’s post-season, and the Jewish high holidays, the challenges confronting presidential debate schedulers are significant. When party conventions are held in late August or early September, the schedule is compressed even more, with the result that debates often cluster into the month of October.

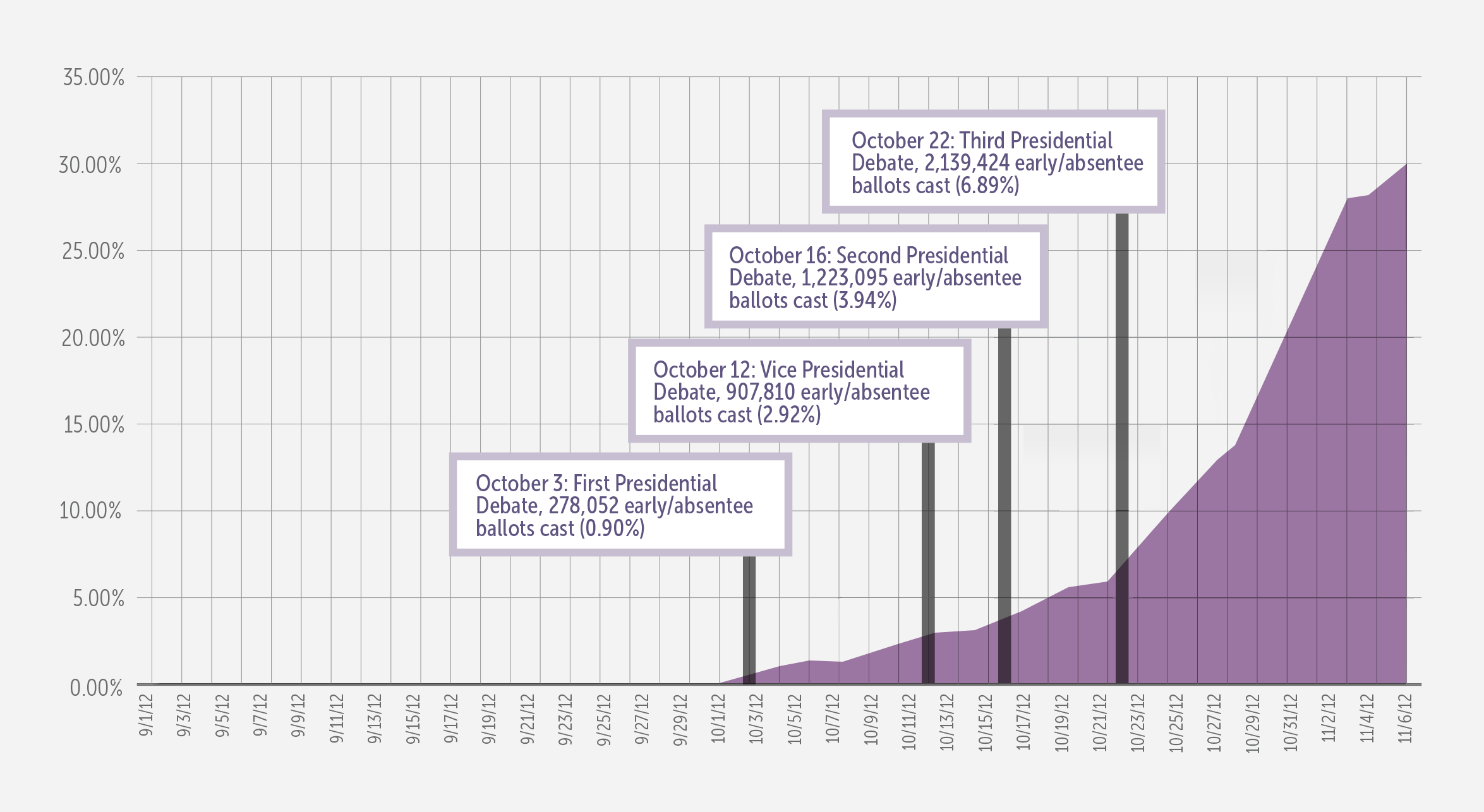

Importantly, the increase in early and no-excuse absentee voting means that October debates occur after balloting has actually begun. In 2012, the percentage of voters who cast ballots before Election Day was 31.6%, according to a Census Bureau study. The affected proportion of the electorate is large. Thirty two states currently allow early voting. Washington and Oregon conduct all of their voting by mail before Election Day. The earliest early voting currently occurs 45 days before Election Day (in South Dakota and Idaho). While the data indicate that only a small percentage of voters voted prior to the first debate in 2012 (0.90%), a more significant number cast their ballots before the third debate (6.89%) (see chart below). Figure 4 shows that the number of absentee and early voters increases rapidly day by day in the last two weeks before the election, which reduces the appeal of having a debate closer to Election Day. Moreover, all of the active duty military and their families living abroad vote absentee well in advance of Election Day.

Since fundraising and university logistics dictate that the Commission pick dates and sites over a year in advance of the election, there is currently no flexibility built into the debate schedule. However, there is precedent for increasing flexibility in scheduling. In 1996, the four Clinton-Bush-Perot debates were held outside of the Commission’s announced schedule over a nine-day period.

In response to increased early voting and the important role the debates play in informing voters about the candidates, the Working Group recommends that:

- The first debate should be scheduled mid-September to give military families and voters who participate in early voting the opportunity to see at least one debate before casting their votes. Sixty-three percent of the respondents in the Hart survey favored moving the first debate to early September before early voting begins.

- The “debate season” of three presidential debates and one vice presidential debate should occur in a window of 19-25 days. The decision on the final schedule for the debates should be set by July 1 of the election year.

- On-site audiences should be dispensed with to eliminate the need for booking sites far in advance and provide greater flexibility in timing and location.

Improving the Transparency and Accountability of the Debate Process

The Memorandum of Understanding

Since the presidential debates are an event held for the benefit of the public, they should be structured to meet basic standards of transparency and accountability. The adjustments necessary to achieve these goals are neither complicated nor controversial.

The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) negotiated by the candidates settles various terms and conditions of the debate (for a synthesis of MOU content, see Appendix Five). In the past, these MOUs have not been made routinely available to the press and public. Because it works out details specific to a given venue and addresses concerns important to the campaigns (e.g., a riser for shorter candidates, whether a candidate can take or bring notes), the MOU is an agreement important to the debate process.

Upon signing, the MOU negotiated by the candidates should be made available to the press and public. The MOU should be posted to the website that the Group recommends be maintained to provide supplemental information about debate topics and to facilitate citizen engagement.

In addition, all the key participants in the debate, including the moderator, should sign the MOU. It makes little sense to have the candidates negotiate understandings that must be enforced by a moderator who is not a party to the agreement. In the past, the moderators, as representatives of the media, have declined to sign the MOU out of a desire to protect their role as journalists who are expected to keep their distance (and objectivity). The Working Group has recommended reforms to address this conflict in role, proposing changes in the role of moderator and in the role of the press generally. In the proposed model, journalists who serve as moderators are working as moderators, not journalists, during the debate: they have agreed to perform the task as a public service, not as an act of reporting. While reporting is unquestionably an act of public service in other contexts, in this one, it presents the live and demonstrated risks discussed in the testimony to the Working Group. While under these proposals members of the press would remain available for selection as moderators, the Working Group concludes that the person who wishes to be a moderator should only do so on the condition that he or she signs the MOU.

Reducing the Debate “Spectacle” and its Cost

The debates have become an extravaganza, elaborate in design and costly. Hosting universities construct temporary buildings or retrofit spaces not just to create a debate venue, but also for spin alleys, candidate holding rooms, surrogate viewing areas, press filing centers, staff work spaces, and ticket distribution. Streets are closed and transportation systems developed to accommodate the movement of Secret Service motorcades and hundreds of audience members to and from the debate site. A television studio is built in the debate hall; technology is installed to give media and the campaigns access to communication systems. Thousands of media, campaign staff, surrogates, and audience members travel to the site. In the hours prior to the debate, corporate sponsors provide food and entertainment for an audience comprising policy makers and influentials. In years past, the debate site supported not just the audience in the hall but also the crowd that gathers for the events surrounding the debate and the surrogates representing the campaigns before and after the debate and available to “spin” the media.

Substantial private funding is needed for a spectacle on this scale. With the private financing comes product promotion and the spending for corporate branding and “goodwill.” How these arrangements are reached, and on what terms, should be a matter of general public interest, but little information is provided or known. Although the overall cost of producing this extravaganza is high, little of it is directly necessary for the main event.

All that is necessary for a presidential debate is a stage for the candidates and a mechanism to transmit their words and images to the public. Other features of current debates including the spin room, the audience, the beer tents, and the locked-down university campus contribute to a spectacle that distracts from the main purpose of the event: the discussion of the major issues among the candidates for president.

No Spin Alley. Other costs now typical of the debate process have become less necessary and useful than in the past. For example, with the rise of social media, the value of “spin alley” has diminished as the senior campaign voices are more likely to use email or Twitter to engage the press both during and after the debate. These changes substantially lessen the need for an elite facility where chosen political spinners and credentialed journalists gather in person to engage in a tired ritual.

No In-Person Audience. The presence of the in-person audience not only raises questions about the seemliness of its composition but its presence carries risks as well. Once the debate begins, despite warnings to remain silent, audience reaction can and has affected the impressions of those viewing at home (See Appendix Five). Laughter, cheers or jeers also magnify moments and distract attention from the substance of the statements made by the candidates. Although it is sometimes said that these eruptions are primarily a problem for primary debates and have been rare in general election debates, there is no reason to assume that this good fortune will last. After all there have been audible audience responses in general election debates: examples include audience reaction to President Reagan’s answer to a question about his age and the response to the exchange between Senators Lloyd Bentsen and Dan Quayle over any comparison of the latter with President John Kennedy. Even one such episode is too many.

Some argue that the presence of a live audience provides positive energy that can bring the best performances out of the candidates. However, the presidential debates that are routinely put forth as the most consequential and substantive ones, the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debates, were held in a TV studio with a very small on-site audience.

There is ample precedent for using a television studio for political debates. In addition to the 1960 debate, the 1976 Carter-Ford presidential debates and the 2010 United Kingdom general election debates were held in studios. Television studio debates are routine for gubernatorial and senatorial elections.

Moreover, as discussed earlier, the audience creates the need for a large logistical footprint that increases the cost of the overall production and raises transparency and accountability issues.

Some point to the presence of students from the host university in the audience as justification. However, the percentage of the audience made up of students relative to donors is small. There are more cost-effective ways to involve students in civic education (generally) and debate education (specifically) than staging a onetime, multimillion-dollar event on campus.

The Annenberg Debate Reform Working Group has presented this analysis and related recommendations in the service of Presidential debates that reflect major changes in our electorate, politics and media. More can and should be done to enrich their content, enlarge their audience and improve upon their accessibility. The members of the Working Group are confident that while views about the particulars will vary, there is likely near‑unanimity about the vital importance of Presidential debates and, therefore, of the need to ensure that they continue to answer the needs of the voters who have watched and listened to them, and to draw into our political process those who have not.

Appendices for this report are available on the supplemental materials page, as well as in the downloadable PDF