How does one bridge science and faith? How does a scientist think about morality or goodness? And where did government scientists succeed – and fail – during the Covid-19 pandemic?

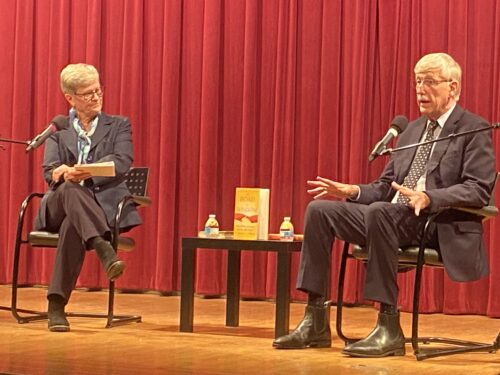

Francis Collins, the geneticist who formerly headed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Human Genome Project, appeared at the Parkway Central Library of the Free Library of Philadelphia recently where he considered these questions and many others in conversation with Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center and a professor of communication at the Annenberg School for Communication.

The Sept. 26, 2024, event, part of the library’s Author Events Series, took the form of a wide-ranging conversation based in part on Collins’ new book, “The Road to Wisdom: On Truth, Science, Faith, and Trust.” An evangelical Christian who came to his faith at age 27, Collins spoke about what he sees as the bridge between faith and science, his work as a leading U.S. scientist during the Covid-19 pandemic, and the fear that keeps him up at night. He also discussed his treatment for prostate cancer, which he wrote about last summer in a Washington Post op-ed. And Collins spoke about Biologos, the organization he founded that aims to show “the many ways that faith and science work hand in hand to address the challenges facing the church and the world today,” and his work with Better Angels, a citizens’ group aiming to bridge the partisan divide between red and blue America.

Jamieson began by quoting from Collins’ book, in which he says he “never encountered a situation where I found my scientific and spiritual world views to be in serious conflict.”

“I’m wondering,” Jamieson said, “if the word serious has any special meaning.”

“This is not going to be a lot of softballs,” Collins replied to laughter, adding that he was honored to be there with Jamieson, “the most significant expert in the field of the research on science communication that exists right now in the United States.”

Collins said that it all comes down to the question that is being asked, and what kind of questions does science ask, and what kind does faith ask, and “which one is being asked, and which tools we should be using to answer them?” If you’re asking about the origins of earth, for instance, you’d best look to science, not the Bible. “God gave us two books,” Collins said, “the book of God’s words, the Bible, which I read almost every day, and the book of God’s works, which is nature. They’re both God’s books. So how can they be in conflict, unless we’re having trouble with the reading?”

Collins also said he found faith in trying to answer questions of morality and human goodness. “When I was struggling with my atheism, trying to figure out what was a more rational approach to the question of God, morality emerged in a very strong way as a pointer – not a proof, but a pointer – towards the idea that there is a source of holiness, and it’s not evolution. It’s something much bigger than that, and that seemed to me to make the greatest sense, a signpost that I was looking for, and a signpost, not just to a God who is an amazing physicist and mathematician in terms of creating the universe, but who cared about me and wanted me to have this same motivation in my heart to try to do the right thing, even though I knew how often I failed.”

Speaking about the power of prayer, Collins said, prayer “is not going to manipulate God into doing [things] my way because that’s probably not a good idea… For me, prayer has often been just trying to get some kind of insight, some kind of conditional understanding of what’s going on…” When praying for someone like his friend, Tim Keller, who is dying of pancreatic cancer, “I don’t expect God to miraculously step in and change everything… but I do pray that it would give him peace about what is happening, and a relief from both anxiety and pain.”

Jamieson and Collins turned to the Covid-19 pandemic. Collins said it was clear by late January 2020 that Covid-19 “was the pandemic we had feared and tried to plan for,” but instead of being influenza, which was expected, it was a coronavirus. “The scientific community rallied to this challenge in a way that I think is absolutely astounding,” he said, and within 48 hours after the genome sequence of the virus had been posted on the internet, the mRNA vaccine that became the Moderna vaccine had been designed by investigators at the NIH in the Vaccine Research Center.

Within 60 days, volunteers were being injected with the vaccine, and after it was shown to be safe, 30,000 volunteers had been enrolled in vaccine trials, he said. The trials found it to be 95% effective, far surpassing the flu vaccine, which is often at 50%. “It was an astounding moment,” Collins said, “and I think history will look at this as being one of the most amazing achievements of science, because in 11 months, the vaccine was produced, which had never been done in less than five years.”

Where the government lost the battle, Collins said, was in its failure to clearly explain to the public the changing science – and subsequent changes in government guidance on various issues, including whether mask-wearing reduces people’s risk of spreading or contracting Covid-19. “What should have been a moment where we had a common enemy, Covid, instead became a moment where we separated off into different categories, many of them driven by politics, and started pointing fingers at each other about not being the right source of truth,” he said.

Messaging from government scientists failed to keep up with the torrent of mis- and disinformation, he said, “and so we lost – badly – that battle.”

One issue that keeps him up at night, Collins said, is what happens if the H5N1 bird flu that is causing outbreaks in poultry and U.S. dairy cows undergoes a mutation and can be passed freely from human to human? And what if it turns out to be as deadly as the 1918 influenza pandemic?

“Anybody who studies public health would say, should that happen, we would have to put in place the strictest kind of way of stopping transmission, by lockdowns, by mask enforcement, by closing schools,” he said. “Otherwise, all kinds of people are going to die who don’t need to. But in our country right now, how will that be received when we are so polarized that even the idea of wearing a mask causes some people’s blood pressure to go off the charts, and now you’re going to be told as a mandate – mandate, really? – it would be the right thing to do. But I think we might have a very hard time.”