The holiday season usually has the lowest monthly suicide rates. While the COVID-19 pandemic has increased risk factors associated with suicide, the media and the public should be careful this holiday season not to make unfounded claims about suicide trends.

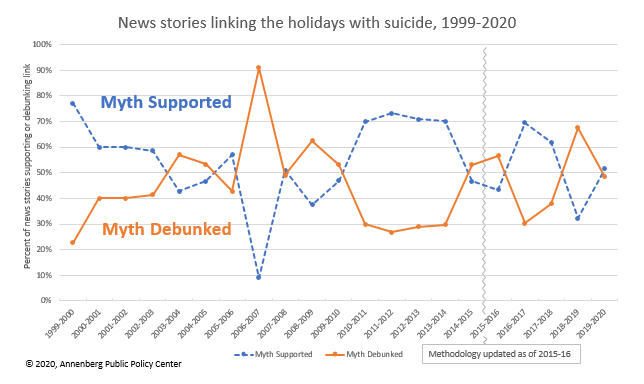

Last year, during the holidays and before the pandemic, about half of the newspaper stories that connected the holidays and suicide contained misinformation falsely perpetuating the myth that suicide increases over the holidays, according to a new analysis by the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania.

“News stories must always be careful not to sensationalize suicide,” said APPC Research Director Dan Romer, who has been tracking holiday-season press coverage about suicide for over two decades. “Creating the false impression that suicide is more likely than it is can have adverse consequences for already-vulnerable individuals. This potential danger is even more critical this year, when COVID-19 has caused hundreds of thousands of deaths in the United States alone.”

Though the pandemic has increased factors associated with suicide such as unemployment, financial stress, and social isolation, there is no clear evidence to date that it has increased the suicide rate, so caution is needed when reporting on this, as noted recently in The Lancet Psychiatry. In addition, a study found that suicide rates did not increase during the Massachusetts lockdown in March, April, and May, while a BMJ editorial reviewing national suicide trends during the early months of the pandemic found either no rise or a fall in suicide rates in high-income countries, including the United States.

Suicide, the myth, and the media

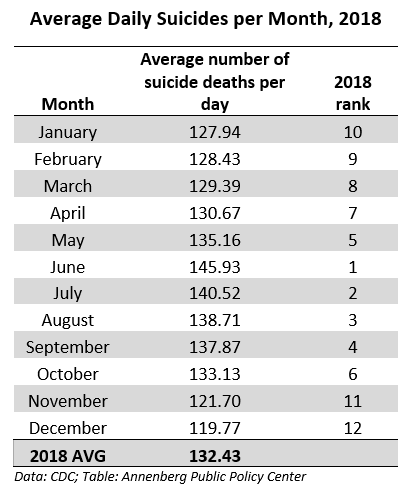

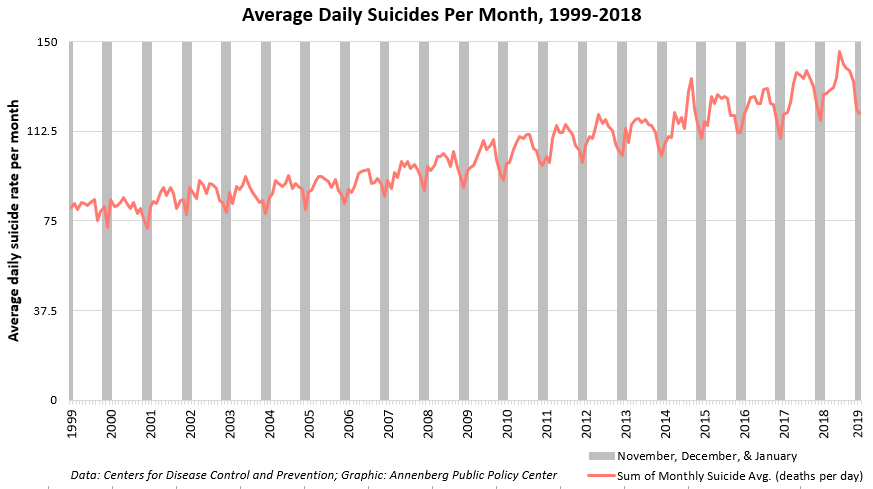

For decades, the holiday season has had some of the lowest suicide rates, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC data from 2018, the latest available, show that the month with the lowest average daily suicide rate was December (12th in suicide rate). The next-lowest rates were in November (11th) and January (10th). In 2018, the highest rates were in June, July, and August – respectively, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd.

The 2019-2020 APPC analysis found that the 33 articles linking the holidays and suicide were almost evenly split – 17 upheld the myth (52%) while 16 debunked it (48%). By contrast, the prior year a greater percentage debunked the myth (68%) than supported it (32%).

APPC has analyzed news coverage of the holiday-suicide myth for 21 years, since the 1999-2000 holiday season. In most years, more newspapers upheld the myth than debunked it. In only three of those years did more than 60 percent of the news stories debunk the myth.

Perpetuating the holiday-suicide myth

Romer noted that the inaccurate stories this year predominantly appeared in smaller news outlets. These stories frequently featured unsupported claims made by community members, columnists, and letters-to-the-editor writers.

“News outlets often publish well-intentioned stories and features at this time of year designed to help people who find the holiday season emotionally difficult,” Romer said. “But they need to be careful to avoid a false connection between the holiday or winter blues that some people experience and suicide. Years of U.S. data show that the suicide rate drops at this time of year.”

The false connection between the holidays and suicide can be seen in examples such as these:

- According to The Aegis, in Bel Air, Md., a councilman from the city of Havre de Grace, Md., “noted that suicides in the wider community tend to increase around the Christmas and New Year’s holidays, so he urged local residents to contact Harford County’s Crisis Hotline…” (December 4, 2019)

- A column in the Eunice (La.) News on “suicide prevention and facts” coming from the parish sheriff’s office says that “there is no single cause for suicide but the risk of suicide often rises during holidays.” (December 14, 2019)

- A “thumbs up, thumbs down” column in the Standard-Examiner of Ogden, Utah, reads in part: “Thumbs down: This time of year can be difficult for many, whether it’s due to a recent family loss, greater sense of loneliness, or other personal struggles. This means it’s typical to see increasing numbers of suicide attempts and death by suicide in Utah.” (December 28, 2019)

- The Hutchinson News in Kansas ran a column on the holiday mood in which the writer said: “Years ago, when I served as a pastoral counselor, in a private therapy practice with two clinical psychologists, our most demanding time was the holiday season. Indeed, suicides spiked during that time of year.” (December 17, 2019)

Debunking the myth

Not all stories make the false connection. For instance:

- In a story about mental health concerns at holiday time, a reporter for the Sun Chronicle (Attleboro, Mass.) included a quote that debunked the myth: “While many believe that more people kill themselves around the holidays, Annemarie Matulis, director of the Bristol County Regional Coalition for Suicide Prevention, said research shows that more people commit suicide in the warmer months. ‘It is a myth that more people die by suicide this time of year,’ Matulis said.” (December 29, 2019)

- A story in the Star-Courier (Kewanee, Ill.) about suicide prevention noted: “According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the holiday months usually have some of the lowest suicide rates, but an Annenberg Public Policy Center analysis of newspaper coverage showed 64% of stories perpetuated the myth that suicides increase during the holidays.” (December 13, 2019)

COVID-19 and Seasonal Affective Disorder

Some news stories discuss the “winter blues” and seasonal affective disorder (SAD). But it is possible to reference the holiday blues without drawing connections to an increase in suicide. For example, a column in November by New York Times health writer Jane Brody successfully described the effects of the seasonal blues without suggesting that it leads to suicide.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to increased stress levels and has left people feeling both more anxious and depressed, Romer said. But in times of stress, people also find support from friends and family that can help to overcome those risks for suicide.

Romer said it’s important that reporters and news organizations debunk the myth, because letting people think that suicide is more likely during the holidays can have contagious effects on individuals who are contemplating suicide. National recommendations for reporting on suicide advise journalists not to promote information that can increase contagion, such as reports of epidemics or seasonal increases, especially when the claim has no basis in fact. These recommendations, developed by journalism and suicide-prevention groups along with the Annenberg Public Policy Center, say that reporters should consult reliable sources such as the CDC on suicide rates and provide information about resources that can help people in need.

Journalists helping to dispel the holiday-suicide myth can provide resources for readers who are in or know of someone who is in a potential crisis. Among those offering valuable information are the CDC (http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/suicide/holiday.html), the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (www.sprc.org) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/suicide-prevention). The U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 800-273-TALK (8255). The Federal Communications Commission has approved a plan to create a three-digit phone number, 988, for suicide prevention but it is not yet in operation.

Methodology

News and feature stories linking suicide with the holidays were identified through searches of both the LexisNexis and NewsBank databases. The searches used the terms “holiday” and “suicide” and (Christmas or Thanksgiving or New Year*) from November 15, 2019, through January 31, 2020.

The search originally used only the LexisNexis database, but was expanded in 2019 to include NewsBank to provide greater coverage of the U.S. press. Using this expanded database search, a reanalysis of prior years, including 2015-16, 2016-17, and 2017-18, did not substantially alter the proportion of stories that debunked or supported the myth.

Researchers determined whether the stories supported the link, debunked it, or showed a coincidental link. Coincidental stories were eliminated. Only domestic suicides were counted; overseas suicide bombings, for example, were excluded.

Thanks go to Lauren Hawkins and Madison Russ, who collected and supervised the coding of the stories, and to Savanna Grinspun, Madeline Ip, Chidi Nwogbaga, and Maria Perilla for assistance in coding. We also appreciate the assistance of Sharon Black of Penn’s Annenberg School for Communication, who provided technical support, and of Alex Crosby and his colleagues at the CDC for providing monthly rates of suicide in the United States.

Download a PDF of this release.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center was established in 1993 to educate the public and policy makers about communication’s role in advancing public understanding of political, science, and health issues at the local, state, and federal levels.