The hospitalization last summer of Dr. Anthony Fauci, former head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with West Nile virus – and his account of it this week in the New York Times – have helped raise public awareness of the dangers of mosquito borne-illness, which can range from Zika and malaria to dengue and West Nile virus.

As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports: “Mild winters, early springs, and warmer temperatures are giving mosquitoes and ticks more time to reproduce, spread diseases, and expand their habitats throughout the United States.” Driven in part by climate change, epidemics from mosquito-spread viruses are occurring with increasing frequency.

As of Oct. 1, 880 U.S. cases of West Nile virus were reported this year, according to the CDC, and West Nile virus continues to be the leading U.S. cause of viral disease spread by insects. West Nile is not the only mosquito-borne disease making headlines. This month, California public health officials warned of an “unprecedented” spread of dengue fever. In August, a New Hampshire man died of the Eastern equine encephalitis, or EEE. CNN summarized: “This summer has brought a flurry of warnings about cases of mosquito-borne illnesses, including malaria, dengue, and Eastern equine encephalitis.”

Yet very few (15%) among the American public worry that they or their families will contract dengue or West Nile virus over the new three months, according to the latest Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) health knowledge survey. This nationally representative panel survey of over 1,700 U.S. adults, conducted in mid- through late September, finds that public knowledge about these mosquito-borne diseases and how to prevent them is spotty.

“As Dr. Fauci’s experience reminds us,” said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center and director of the survey, “you don’t have to travel to exotic places to come in contact with mosquitoes able to cause serious illness. They may be lurking in your own backyard.”

Ways of contracting dengue fever and West Nile virus

Infected mosquito (yes): People can become infected with dengue fever or West Nile virus by the bite of an infected Aedes mosquito. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of those surveyed know that it is through this vector that scientists think it is likely one can be infected with these viruses.

Sneezing and coughing (no): Many people are uncertain about whether scientists think someone can become infected with dengue fever or West Nile Virus from being sneezed or coughed on by someone who is infected with the viruses. People do not get infected this way, the CDC says, but only a third (34%) say scientists think it is unlikely people can get it this way. A quarter (26%) think, incorrectly, that scientists believe this is a way to become infected and 39% are not sure.

Knowledge of West Nile virus symptoms

Despite the finding that most people know one can become infected with dengue fever or West Nile virus via a mosquito bite, many are unaware of the symptoms of West Nile virus. When presented with a list of symptoms, both true and not, well under half selected the symptoms of West Nile virus identified by the CDC.

The percentage of people who chose these CDC-identified symptoms of West Nile virus:

- 42% fever

- 37% muscle and joint pain

- 36% headache

- 29% nausea and vomiting

- 22% rash

And the percentage who incorrectly chose these, which are not symptoms of West Nile virus:

- 28% dizziness or lightheadedness

- 11% firm, round, painless sore

Beliefs about contracting dengue fever and West Nile virus

Scientists are using genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes to control the mosquito population in parts of the world, including Brazil, Panama, and India. These GM mosquitoes are produced so that the female offspring do not survive into adulthood, limiting the size of the population and helping to minimize the spread of mosquito-borne illnesses.

In our survey, few respondents (16%) believe that genetically modified mosquitoes have caused dengue fever outbreaks, while 36% correctly know this is false and 48% are not sure. More people believe genetically modified mosquitoes could be helpful in minimizing the spread of dengue viruses: 36% say this statement is true and 16% say it is false. As with the negative effects of the genetically modified mosquito, 48% are not sure whether this is true or false.

According to the CDC, the Aedes mosquito, which carries the dengue virus, is not found in every state in the continental United States. Nearly 4 in 10 people (38%), however, incorrectly believe that these mosquitoes can be found in every state of the continental United States. More than a fifth (22%) correctly say that statement is false and 40% are not sure.

- Preventing dengue and West Nile virus: Nearly 8 in 10 (79%) correctly believe that the best defense against dengue and West Nile virus is by preventing mosquito bites and controlling mosquitoes in or around the home, while 17% percent are not sure, and 4% percent believe that statement to be false.

- Antiviral treatment: Currently there is no antiviral treatment for dengue fever or West Nile virus. Only about a quarter (23%) know this is true, 15% believe it to be false, and most (62%) are not sure.

Taking precautions against mosquito bites

The CDC advises individuals to take steps to protect themselves from mosquito bites that can make them sick. In our survey, about 6 in 10 people (59%) say they routinely take precautions to avoid getting mosquito bites at any time of year – significantly fewer than the roughly two-thirds (67%) who said so in an APPC survey conducted in the summer of 2016 during the Zika outbreak. Over a third today (37%) say they do not routinely take precautions.

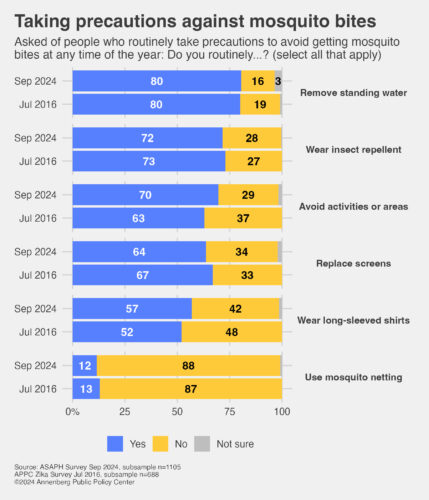

Among those who say they routinely take such precautions today, we asked each to indicate what they do from a list of actions:

- The precaution which most say they take to avoid getting mosquito bites is to remove standing water (80%), followed by wearing insect repellent (72%). Both percentages are unchanged from when we previously asked about them, in July 2016.

- Seven in 10 (70%) avoid activities or areas that would bring them in contact with mosquitoes, a significant increase from the 63% who said this in July 2016.

- 64% say they routinely replace or repair window screens, unchanged from July 2016.

- 57% say they wear long-sleeved shirts or other protective clothing outdoors, significantly higher than the 52% who reported doing this in July 2016.

- Few (12%) routinely use mosquito netting, about the same as July 2016.

Applying insect repellent on top of sunscreen

Insect repellent is one of the primary ways to prevent mosquito bites, but when outside in the sun, it is also important to apply sunscreen to protect against harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays. We asked respondents what the CDC recommends as the proper way to apply both insect repellent and sunscreen together.

Generally, about 3 in 10 respondents (29%) correctly know that the CDC recommends that one should put on sunscreen and let it dry before putting on insect repellent. Very few (5%) say that the CDC recommends the opposite (insect repellent first, then sunscreen) and 16% think the CDC guidance is that it does not matter in which order you put on sunscreen and mosquito repellent, but you should use both if you are in an area with mosquitoes. Both of these responses contradict what the CDC advises. Half (50%) are not sure what the CDC advises on this.

Applying insect repellent on exposed skin, not under clothing

The CDC advises people not to apply insect repellent on the skin under their clothing. Just 13% know that this is what the CDC recommends. Nearly half in total either say that the CDC recommends that people put insect repellent on their body and then put clothes on over the areas protected by the repellent (19%) or that the CDC says it does not matter whether you put repellent under your clothing (29%) but one should use insect repellent if they are in an area with mosquitoes. Four in 10 (39%) are not sure what the CDC recommends regarding this.

Forgoing insect repellent on young infants

Just over half of respondents (52%) indicate, correctly, that the CDC recommends that insect repellent should not be used on infants younger than 2 months old, but rather they should be dressed in clothing that covers their arms and legs and place mosquito netting over their cribs, strollers, and baby carriers. Under half (45%) say they are not sure of the CDC recommendation for applying insect repellent to an infant. Three percent incorrectly think the CDC recommends that insect repellent can be used on babies younger than 2 months old, which the CDC does not recommend.

Using an EPA-registered insect repellent

The CDC recommends that people look for an insect repellent that is registered with the EPA – a fact that just over 1 in 5 people (21%) know. Nearly a third of those (29%) surveyed think that the CDC’s recommendation on insect repellents is to use a product with over 50% DEET, while 6% think the CDC says to look for an insect repellent that says it is natural. A plurality (43%) is not sure what the CDC recommends on this question.

DEET is the active ingredient in many insect repellents. While products with higher concentrations of DEET may last longer, the CDC says products containing 50% or more DEET provide no better protection than those with a lesser concentration of DEET.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center’s ASAPH survey

The survey data come from the 21st wave of a nationally representative panel of 1,744 U.S. adults conducted for the Annenberg Public Policy Center by SSRS, an independent market research company. Most have been empaneled since April 2021. To account for attrition, small replenishment samples have been added over time using a random probability sampling design. The most recent replenishment, in September 2024, added 360 respondents to the sample. This wave of the Annenberg Science and Public Health Knowledge (ASAPH) survey was fielded Sept. 13-22 and Sept. 26-30, 2024. The margin of sampling error (MOE) is ± 3.5 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. All figures are rounded to the nearest whole number and may not add to 100%. Combined subcategories may not add to totals in the topline and text due to rounding.

Download the topline and the methodology.

The data analysis for this news release was conducted by Ken Winneg, Ph.D., APPC’s managing director of survey research.

In addition to Jamieson and Winneg, the Annenberg Public Policy Center team on the Annenberg Science and Public Health (ASAPH) knowledge survey comprises APPC data analysts Laura Gibson, Ph.D., and Shawn Patterson Jr., Ph.D., and Patrick E. Jamieson, Ph.D., director of APPC’s Annenberg Health and Risk Communication Institute. The ASAPH Knowledge Monitor is a project of APPC’s Annenberg Health and Risk Communication Institute, which is funded by an endowment established for it by the Annenberg Foundation.