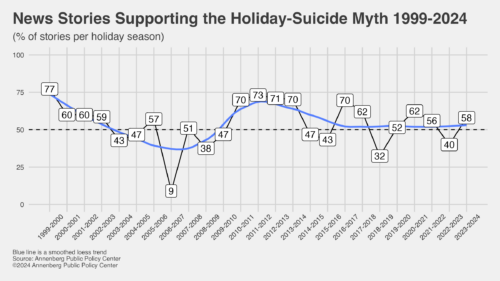

As in most years that we’ve followed news reporting about the myth that suicides peak during the end-of-year holidays, an analysis of the past year showed again that more newspaper accounts supported the false idea that the suicide rate increases during the holiday season than debunked it.

Over the past 25 years that we have been studying this phenomenon, in just over a third (nine years or 36%) have we found more debunking of the myth than support for it. Despite years of debunking by mental health researchers, journalists, and others, the misconception that people are more likely to die by suicide over the holidays has shown remarkable persistence.

Last year, over the 2023-24 holiday season, a search of media stories found 26 newspaper stories linking the holidays and suicide, of which 15 (58%) upheld the myth and 11 (42%) debunked it.

“For more than a generation, we’ve been analyzing how the news media report on the mistaken belief that the suicide rate increases over the holiday season,” said Dan Romer, research director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania. “The persistence of this myth suggests that its hold on the public’s imagination is difficult to undo. Supporting the myth serves no useful purpose and may have a contagious effect on vulnerable people who are experiencing a crisis and contemplating suicide during the holidays.”

The news media are not the only ones who commonly get it wrong. In a nationally representative survey we conducted in 2023, 4 out of 5 adults incorrectly picked the month of December over several other months as the “time of year in which the largest number of suicides occur” – even though the other months provided as potential choices typically have much higher suicide rates.

Associating the holidays with suicide

Some of the newspaper accounts supporting the myth last year ran in local, relatively smaller publications. Some cited the mistaken beliefs of well-meaning community authority figures. All of these promoted the false myth:

- A Denver Post story on Dec. 8, 2023, concerning four murder-suicides in two weeks, quoted a local social-services official as saying that the “ongoing holiday season could be part of the reason why.”

- A columnist for the Advertiser-Gleam, in Guntersville, Ala., wrote on Nov. 28, 2023, about taking his annual trip to cut the Christmas tree. The columnist wrote: “Statistics inform us that during the holiday season the number of suicides increase. It is easy to see why. Each year we mark another year has passed and we are a year older. Each year brings the loss of some we love and new additions that we have come to love…”

- Northern Sentry, the Minot Air Force Base (N.D.) newspaper, published a story from Air & Space Forces Magazine saying that the Air Force base was investigating the deaths of three airmen in one month. The Dec. 1, 2023, story quoted a military spouse as telling the Minot Daily News that the “holidays are such a vulnerable time for people, where we have some of the highest rates of suicide in general.”

Our media analysis also found examples of stories that debunked the myth. Among these:

- In the Dec. 21, 2023, story, “These tips will help you navigate your holiday blues,” the weekly New Pittsburgh Courier quoted a mental health professional from the Washington University School of Medicine, in St. Louis, who said, “It’s unfortunate that the myth that suicide rates increase around the winter holidays continues since studies have shown that’s just not the case… let’s not sensationalize the risk of suicide, or give people the impression that this is a time when more people are dying by suicide.” The story added: “In her view, emphasizing this false risk can be harmful, potentially influencing those who are struggling and making it seem like a more prevalent occurrence.”

- A column by Dr. Barton Goldsmith in the Grand Island (Neb.) Independent, on Dec. 9, 2023, begins: “There has been a long-standing myth that suicide rates increase over the holiday season. According to the Mayo Clinic this is completely false. What is true is that the rates of depression and stress do increase. Here are 10 solid tools to help you and deal if Santa also brings you some holiday blues.”

“As these two stories observe, the holiday blues are a real phenomenon that might require attention to loved ones who might be sad at this time of year,” Romer said. “People may feel sadness around the holidays for many different reasons. There’s no need to give people the false impression that others are dying by suicide, when that could actually lead to contagion.”

As we’ve noted in our annual news releases on this research, national recommendations for reporting on suicide advise journalists not to promote information that can increase contagion, such as reports of epidemics or seasonal increases, especially when the claim has no basis in fact. The recommendations, which were developed by journalism, mental health, public health, and suicide-prevention groups, along with the Annenberg Public Policy Center, say that reporters should consult reliable sources such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Journalists helping to dispel the holiday-suicide myth can also provide valuable resources for readers who are in or know of someone who is in a potential crisis, including those at the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, or SAMHSA.

The seasonal nature of the suicide rate

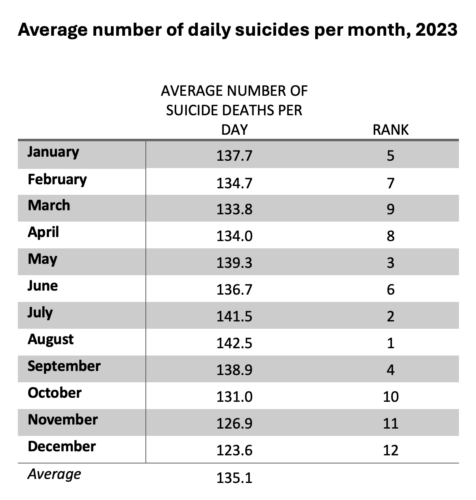

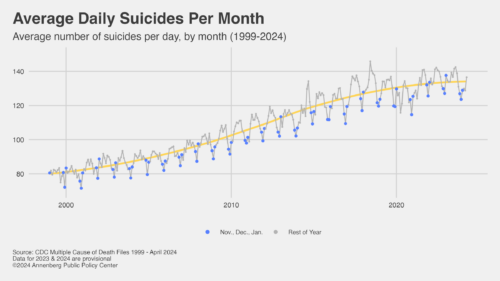

CDC data show that the months with the lowest average daily suicide rates are typically in the fall and winter: November, December, and January.

In 2023, the last full year for which CDC data are available, December had the lowest average daily suicide rate – it was 12th among the months, and November was 11th. January came in 5th. The months with the highest rates were August (1st) and July (2nd).

This seasonal pattern for the suicide rate holds true in Australia, too. Romer last year conducted an analysis of average daily suicide rates over a dozen years in Australia. He found that the winter months in Australia had lower suicide rates, similar to the United States. Since Australia is in the southern hemisphere, the month with the lowest average daily suicide rate was June, which is the beginning of winter there.

In releasing the Australian data last year, Romer said, “This helps to explain the lower suicide rate we see here in December – it’s mostly due to the onset of the winter season. Psychologically, because of the shorter and gloomier days of winter in the U.S., we tend to associate them with suicide. But that’s not what happens in reality.”

Not enough people know about 988

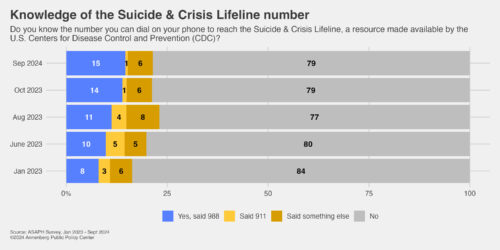

A major government initiative to help vulnerable people occurred in July 2022, when the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline was renamed the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, and 988 was implemented as its three-digit nationwide phone number. Annenberg Public Policy Center surveys have found that familiarity with the 988 number is growing slowly, and still too few people know it.

As of the September 2024 nationally representative panel survey, just 15% of U.S. adults are familiar with the suicide lifeline, up from 11% in August 2023. These are people who said they were aware that there is a suicide lifeline number and, in an open-ended format, said it is 988.

“The help that can be found at the 988 helpline can only save lives if those in need and their loved ones and friends know the number,” Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, said last month when this finding was released. “When 988 is as readily recalled as 911, the nation will have cause to celebrate.”

How we conducted this media study

News and feature stories linking suicide with the holidays were identified through searches of the LexisNexis and NewsBank databases combining the term “suicide” with words such as “holiday,” “Christmas” and “New Years,” (with the addition of terms such as “increase” in NewsBank) from November 15, 2023, through January 31, 2024. Researchers determined whether the stories supported the link, debunked it, or made a coincidental reference. Stories with a coincidental reference were eliminated. Only domestic suicides were counted.

APPC’s Sam Fox supervised the coding of the stories, working with Lauren Hawkins. The coding was done by Penn students Kendall Allen, Nicholas Bausenwein, Ginger Fontenot, Sienna Horvath, Nia Peterson, and Dylan Walker, who are with APPC’s Annenberg Health and Risk Communication Institute. Shawn Patterson created the data figures.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center was established in 1993 to educate the public and policy makers about communication’s role in advancing public understanding of political, science, and health issues at the local, state, and federal levels.