While the nation was in the grips of the Covid-19 pandemic during last year’s holiday season, not many in the media were focused on possible links between the holidays and suicide trends.

That is one inference that may be drawn from the latest data collected by the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania in its annual analysis of news reporting about the holiday-suicide myth, the false claim that the suicide rate increases at holiday time.

In 2020, for the second year in a row, the U.S. suicide rate declined. And in the 2020-21 holiday season, there were not many newspaper stories – fewer than 20 – that connected the holidays and suicide trends, either debunking or perpetuating the myth. The suicide rate does not increase during the year-end holiday season; in fact, it decreases.

“Although many stories during the pandemic concerned the increase in risk factors for suicide such as anxiety, social isolation, and unemployment, it was encouraging to see that few news media stories drew a seasonal connection with suicide,” said Dan Romer, APPC’s research director.

Suicide and the holiday-suicide myth

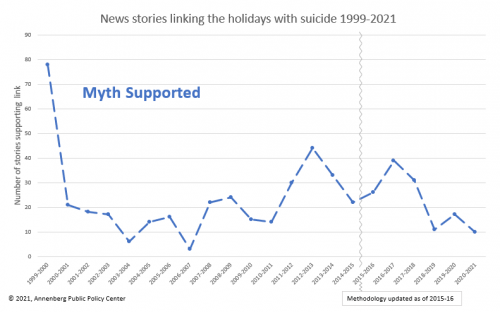

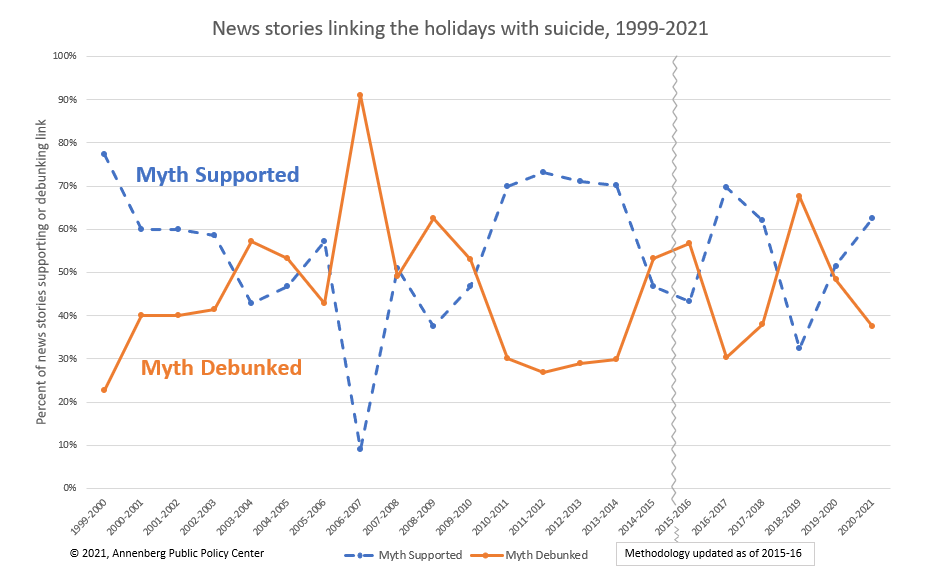

For two decades, APPC has analyzed newspaper stories that linked the holidays and suicide to see whether they perpetuated or debunked the holiday-suicide myth. Over the 2020-21 holiday season, only 16 stories referenced a connection, with 10 perpetuating the myth (63%) and six debunking it (37%) – among the lowest total counts since APPC has tracked this.

“This is a success story, in a sense,” Romer said. “Given the concerns about mental health during the pandemic, we could have seen a lot more stories making the connection with suicide, but we didn’t. In last year’s report on the holiday-suicide myth, we advised media organizations to be careful not to sensationalize suicide during the pandemic or create the false impression it was more likely than it is. Now, we are encouraged to see that the suicide rate decreased during the pandemic and that few stories during the pandemic holiday season supported the myth.”

Declining suicide rate

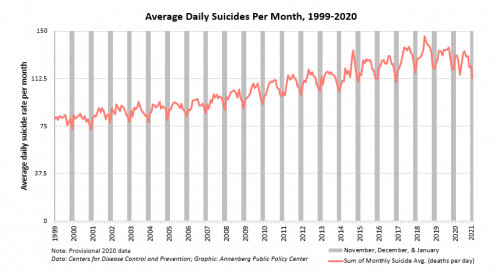

Despite the increase in some risk factors associated with suicide, provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that the number of suicides in 2020 declined. In the United States, from 1999 to 2018, the suicide rate increased 35%, according to the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, for an average of 1.75% per year. But in 2019 the suicide rate dropped 2% and in 2020 it dropped 3%, the CDC reported.

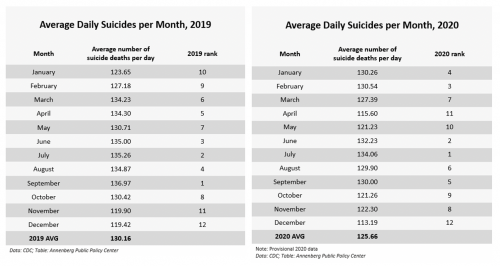

In both 2019 and 2020, December ranked last (12th) among months for average daily suicides, as it usually does. In 2019, November and January had, respectively, the 11th and 10th lowest suicide rates, as is also common. But in 2020, the next-lowest average months were April and May, the first full months of pandemic lockdowns in parts of the U.S.

“This is especially noteworthy given the lockdown,” Romer observed. “People were hunkered down with their families and experiencing the stress together, which may have lessened the risk for suicide among those who were most vulnerable. One of the potential risk factors for suicide is a feeling of being a burden to others. That might be true for someone who is suddenly unemployed. But if many are in the same boat, you’re not a burden – you’re the same as everyone else is, experiencing the crisis.”

High anxiety

At the same time, there’s no question the pandemic brought high levels of anxiety, especially for young people.

In 2020 and 2021, 38% to nearly 52% of 18- to 29-year-olds reported having symptoms of anxiety or depression that are “shown to be associated with diagnoses of generalized anxiety disorder or major depressive disorder,” according to surveys conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics. In the Thanksgiving holiday period from November 25-December 7, 2020, 49% of 18- to 29-year-olds reported symptoms of anxiety or depression, more than other age groups. The national average in that period for all ages was 36.1%. By contrast, the full-year average in 2019 for all ages was 10.8%.

Perpetuating or debunking the holiday-suicide myth

APPC has analyzed news coverage of the holiday-suicide myth over 22 holiday seasons, from 1999-2000 through 2020-21. In most years, more newspapers upheld the myth than debunked it. Although more stories upheld the myth this year, the overall dearth of coverage with this focus may be seen as a positive sign.

“There was less suicide in 2020, and the press didn’t hype it during the holidays,” Romer said. “People may suffer from seasonal affective disorder or experience what is often called ‘the holiday blues,’ but that doesn’t mean you will see a rise in holiday-season suicide.”

The false connection between the holidays and suicide can be seen in stories such as:

- The Tribune-Democrat of Johnstown, Pa., story “Therapists: Isolation, stress of pandemic taking toll,” which quoted one therapist saying, “Holidays bring up good and bad. It’s a real trigger time of the year. Suicide rates go up this time of year. Suicide rates have already doubled. People are feeling helpless again and hopeless. They’re feeling unsupported as well.” (December 23, 2020)

- A front-page story about an increase of fatal overdoses in the Pittsburgh (Pa.) Post-Gazette that noted: “Health officials are also warning Pennsylvanians that depression and suicide rates can spike during the holiday season.” It does, however, add that “Suicide rates have been a particular source of worry during the pandemic, but annual numbers in Allegheny County have not shown an increase.” (December 20, 2020)

One story debunking the myth:

- The South Bend (Ind.) Tribune’s front-page story “Pandemic exerts mental toll” quotes the spokeswoman for a suicide prevention coalition as saying, “Part of the reason suicides are lower over the holidays is because that’s the one time of the year when we tend to reach out to family and friends, and I think we’ve seen some of that during the pandemic.” (December 31, 2020)

Dispelling the myth and offering help

Romer said it’s important that reporters and news organizations debunk the myth. Allowing people to think that suicide is more likely during the holiday season can have contagious effects on people who are contemplating suicide. National recommendations for reporting on suicide advise journalists not to promote information that can increase contagion, such as reports of epidemics or seasonal increases, especially when the claim has no basis in fact. These recommendations, developed by journalism and suicide-prevention groups along with the Annenberg Public Policy Center, say that reporters should consult reliable sources such as the CDC on suicide rates and provide information about resources that can help people in need.

Journalists helping to dispel the holiday-suicide myth can provide resources for readers who are in or know of someone who is in a potential crisis. Those offering valuable information include the CDC, the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 800-273-TALK (8255). The Federal Communications Commission has approved a plan designating the three-digit phone number 988 for suicide prevention calls, to be implemented by July 16, 2022.

Methodology

News and feature stories linking suicide with the holidays were identified through searches of both the LexisNexis and NewsBank databases. The searches used the terms “holiday” and “suicide” and (Christmas or Thanksgiving or New Year*) from November 15, 2020, through January 31, 2021. APPC’s search was originally run on the LexisNexis database but was expanded in 2019 to include NewsBank for wider coverage of the U.S. press. A reanalysis of past years since 2015-16, including NewsBank, did not substantially alter the proportion of stories debunking or supporting the myth. Researchers determined whether the stories supported the link, debunked it, or showed a coincidental reference. Coincidental stories were eliminated. Only domestic suicides were counted; overseas suicide bombings, for example, were excluded.

Lauren Hawkins and Madison Russ collected and supervised the coding of the stories, and Thomas Christaldi, Savanna Grinspun, Sienna Horvath, Madeline Ip, Chidi Nwogbaga, Maria Perilla, and Tara Shilkret did the coding.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center was established in 1993 to educate the public and policy makers about communication’s role in advancing public understanding of political, science, and health issues at the local, state, and federal levels. Find @APPCPenn on Twitter and Facebook.