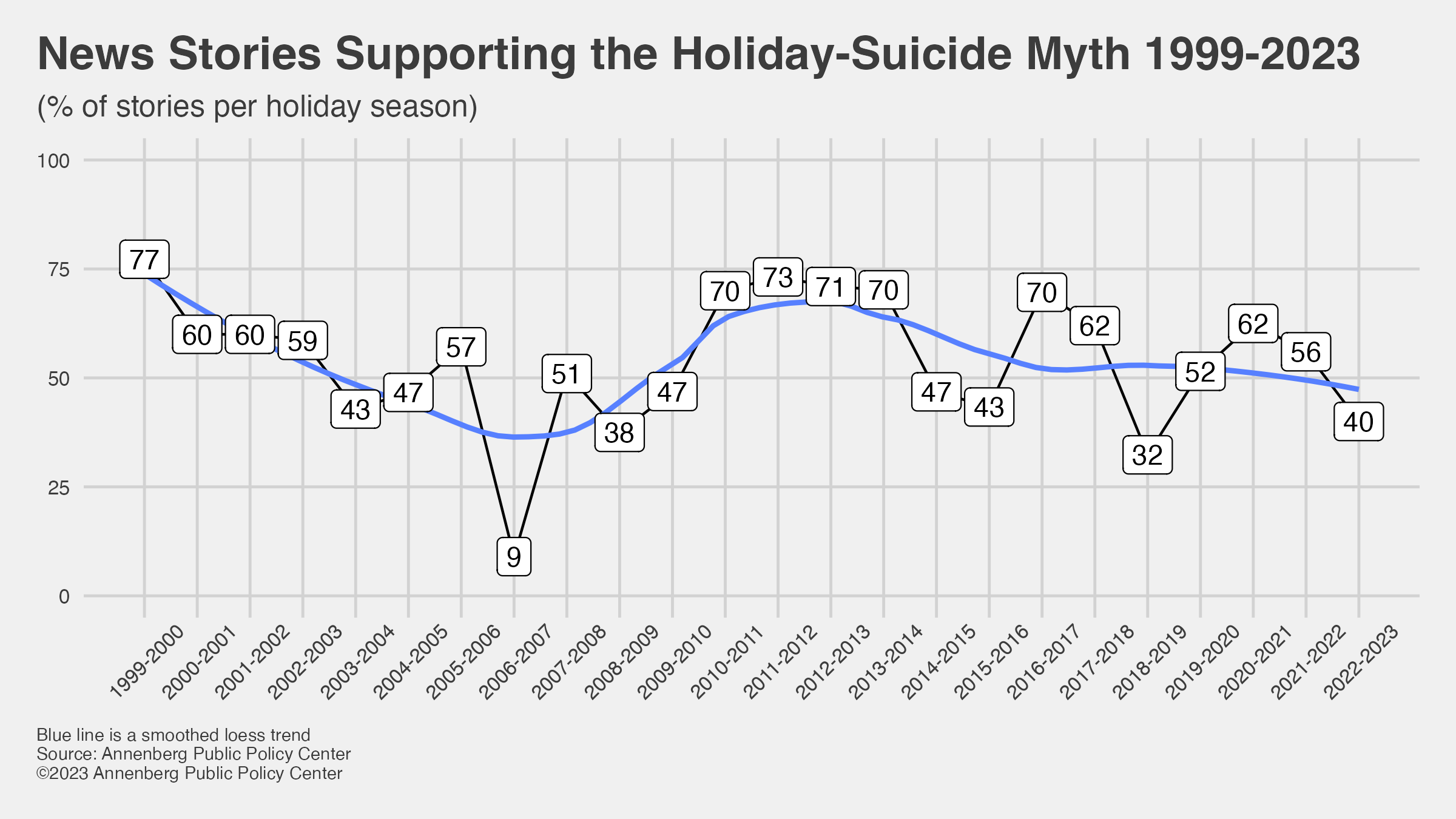

For more than two decades, the Annenberg Public Policy Center has tracked the ways in which news organizations erroneously link the year-end holiday season with suicide, perpetuating the false holiday-suicide myth. But as years of national data show, the winter holiday months usually have low average daily suicide rates, with December the lowest of all.

In our new media analysis, we find that of the newspaper stories during the 2022-23 holiday season that explicitly connected the holidays with suicide, 60% correctly debunked the myth while 40% incorrectly supported it.

But it’s not just the media that often gets it wrong. So does the public.

In a separate, nationally representative survey we conducted earlier this year, 4 out of 5 adults incorrectly picked the month of December over several other months that typically have much higher suicide rates as the “time of year in which the largest number of suicides occur.”

“We are encouraged to see more news stories that debunked the myth than supported it,” said Dan Romer, research director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania. “But whether it’s the media that is influencing popular opinion, or mistaken beliefs by the public that appear in news stories, it’s unfortunate to see there are still persistent misimpressions about the holidays and suicide.”

APPC has sought for decades to correct the popular misconception linking the holidays with suicide by doing a content analysis of newspaper stories to see whether they perpetuated or debunked the myth. In the 2022-23 holiday season, 35 stories drew a link between the holidays and suicide, of which 21 debunked the myth (60%) and 14 perpetuated it (40%). A smaller percentage of news stories upheld the myth than in the prior three seasons (see Fig. 1).

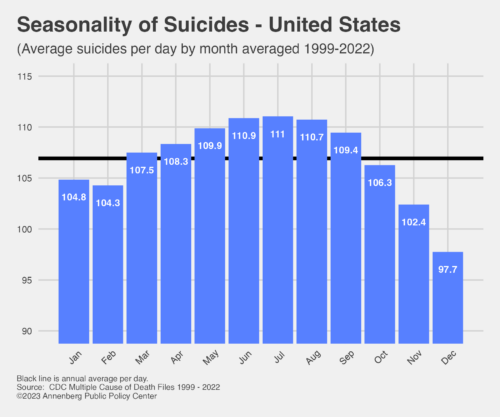

The seasonal nature of the suicide rate in the U.S.

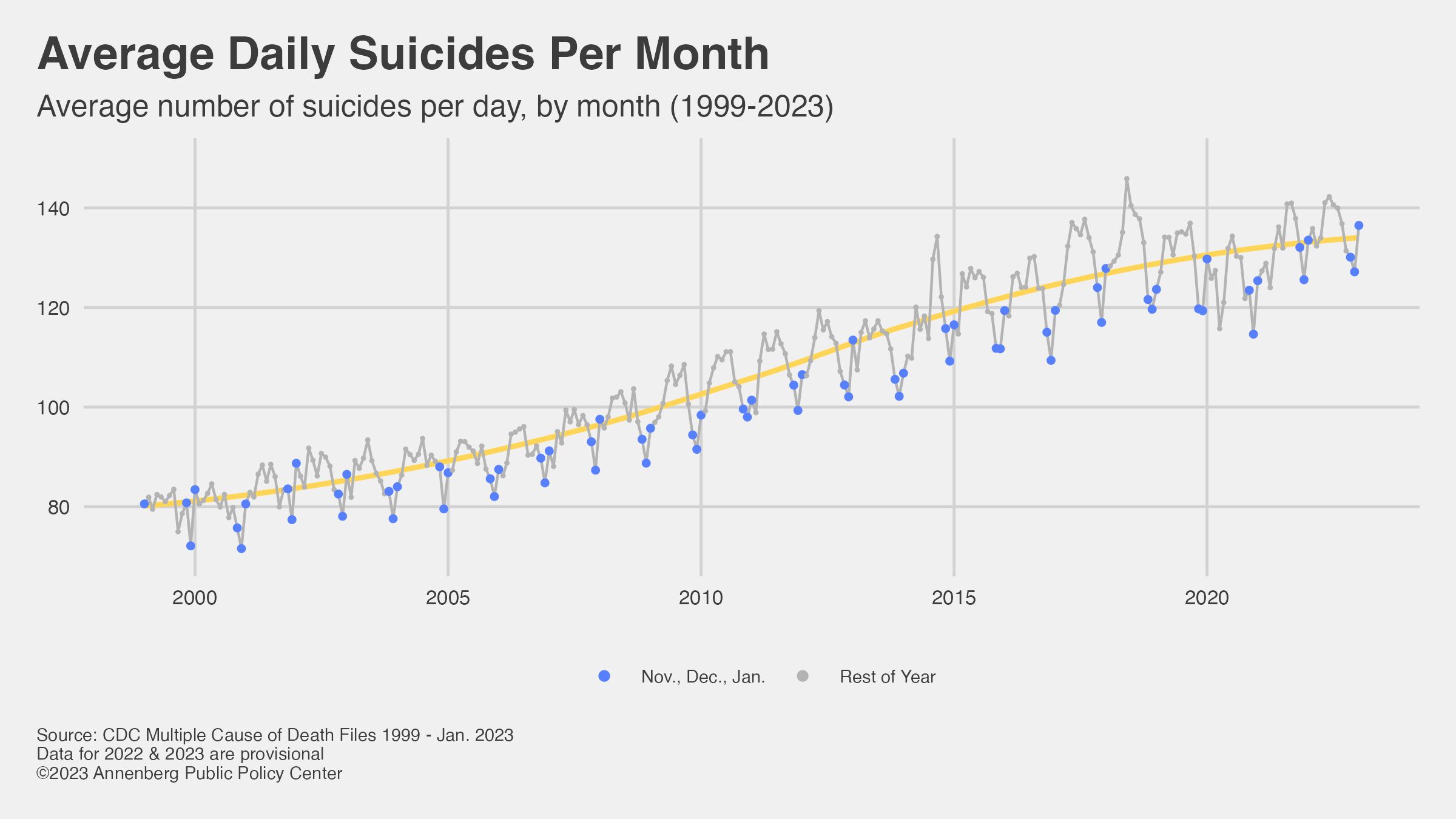

Provisional data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that the number of U.S. suicides increased in 2022 for the second consecutive year following two years of declines. From 2021 to 2022, the number of U.S. suicide deaths increased by 2.6%, reaching a record of nearly 50,000, according to the CDC. It is likely to grow when final figures are in.

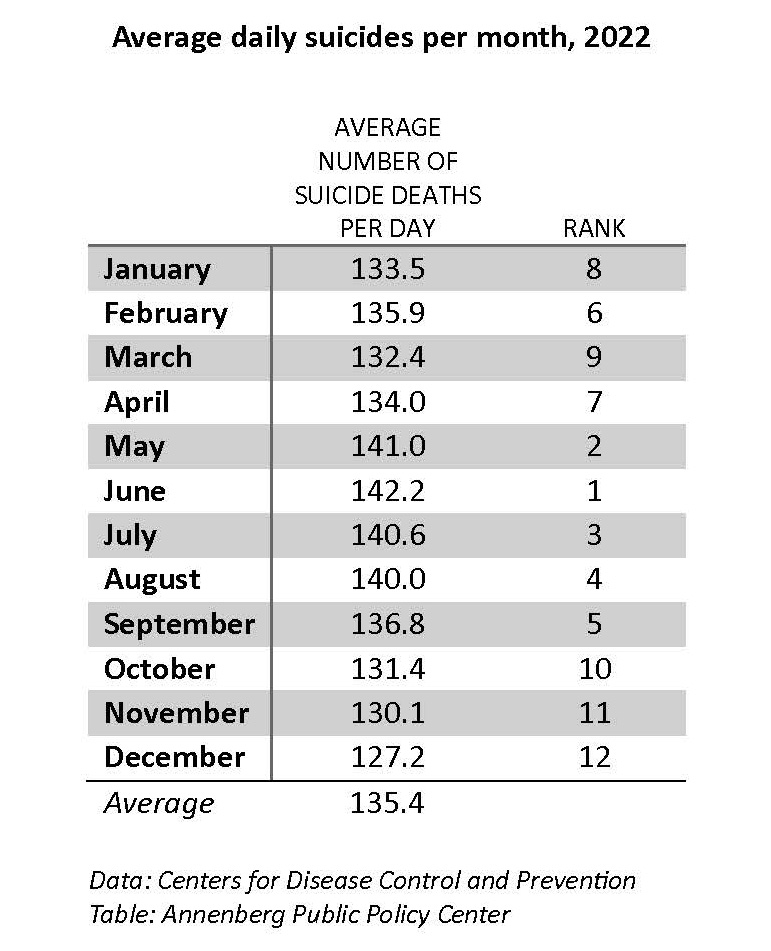

In 2022, the average number of U.S. suicide deaths per day in November and December made those the lowest months of the year – 11th and 12th, respectively – and January was ranked 8th.

While the late fall and winter had the lowest average number of suicide deaths per day in 2022, the late spring and summer months had the highest numbers. May, June, July, and August were, respectively, 2nd, 1st, 3rd, and 4th, in average suicides per day (see Figs. 2 & 3).

“The holiday season is undoubtedly a difficult time of year for some,” Romer said. “We see news stories, health features, and advice columns on seasonal affective disorder and the holiday blues. We see the reemergence of holiday movies like ‘It’s a Wonderful Life,’ and the media and many individuals reflect on the year past, contemplating what has been lost. But people are incorrect to conclude that the fraught nature of the season results in an increase in suicide.”

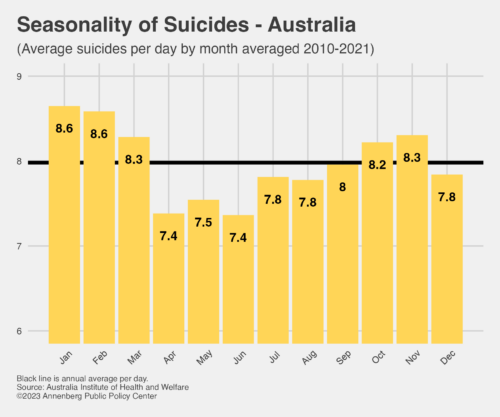

Seasonal suicide rates are reversed in Australia

Romer conducted an analysis of monthly suicide data in Australia, which is in the southern hemisphere, where the seasons are reversed from those in the United States. In the southern hemisphere, December through February are summer months. Romer found that the seasonal pattern of suicide death holds in Australia, too – but it’s the reverse of the United States.

In Australia, the late spring and summer months of November through March have higher rates of suicide deaths, with the highest rates during the mid-summer, in January and February. The lowest average daily suicide rate was in June – the beginning of winter in Australia (see Fig. 4). (The pattern in Australia has been shown to be true in Brazil, as well.)

“The increases and decreases in the suicide rate are largely seasonal,” Romer said. “The reason it’s low around the U.S. holidays is because it is winter here, and the suicide rate tends to be lower in the winter. If you go to Australia, where it is summer in December, you will see a higher rate – and that is true for summer here in the United States, too.

“This helps to explain the lower suicide rate we see here in December – it’s mostly a seasonal thing,” Romer added. “Psychologically, because of the shorter and gloomier days of winter in the U.S., we tend to associate them with suicide. But that’s not what happens in reality.”

A survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center in January 2023 supports the idea that in the United States, people overwhelmingly associate December with suicide. In the survey, 1,657 U.S. adults were given a choice of five months and asked which time of year they thought the largest number of suicides occur. Of those surveyed, 81% chose December, even though the other months (April, June, August, October) typically had higher average daily suicide rates over the past 20 years, and December never had the highest rate in that period.

“Our survey results show why journalists often encounter people associating the winter holidays with suicide,” Romer said. “Most people suppose December to be the highest-risk month for suicide. It is also likely that the advice that columnists give to readers about how to cope with the holiday blues and stress adds to the mistaken impression.”

How the media cover the holiday-suicide myth

APPC has analyzed news coverage of the holiday-suicide myth over two dozen holiday seasons, starting with the 1999-2000 season through 2022-23. For most of those years, more newspaper stories supported the myth than debunked it, though that was not the case in 2022-23.

The false connection between the holidays and suicide can be seen in stories such as these:

- A Houston Chronicle story on Dec. 9, 2022, “Suicides at border prompt effort to boost mental health aid,” concerns bipartisan efforts by U.S. Rep. Tony Gonzales (R., San Antonio) and other legislators to provide more mental health resources to the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol after a number of agent suicides. The story paraphrases Gonzales as saying that “it’s especially important for lawmakers to help agents this month since suicides usually spike around the holidays.”

- (While it is important to provide mental health resources to these officers, the need is also great at other times of the year.)

- In a Dec. 23, 2022, column on holiday film favorites, a writer for the Owensboro (Ky.) Messenger-Inquirer chooses “It’s a Wonderful Life,” praising the “bold move for a Christmas movie in the 1940s to center around a suicidal man during the holidays.” But the item says the holidays “are a time where many feel depressed and the suicide rates increase.”

- A U.S. Navy veteran who is fund-raising to help veterans cope with mental-health issues says in a Christmas Eve story in The (Ashtabula, Ohio) Star Beacon that “Christmas is the highest time for suicides.”

More stories this year debunk the myth, including some that mention the CDC or the Annenberg Public Policy Center. “We were heartened to see that our efforts have been cited by some of these news outlets,” said Romer. Among these stories:

- The Chicago Daily Herald, in a story on “How to combat holiday blues,” which ran on Dec. 24, 2022, notes: “While December sees the lowest suicide rates, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the holidays often bring stressors that can trigger depression, anxiety or loneliness.”

- In a Nov. 21, 2022, story on a holiday-stress mental health webinar hosted by a Los Angeles County supervisor, a writer for The (Santa Clarita, Calif.) Signal, said: “While suicides have increased since the pandemic, suicides do not increase in rate during the holidays, according to the Centers for Disease Control. In fact, it actually decreases. The CDC has labeled this a myth…”

- In “Research center warns of holiday suicide myth,” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote on Christmas Day 2022 about APPC’s efforts to combat the myth: “More than two decades ago, the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania decided to make recommendations to journalists on how to cover suicides. In the course of developing them, researchers there found the widely-reported story that suicides jump around the holidays was actually a myth: suicides are no more common in the holiday season than any other time of year.”

Why news media should not support the holiday-suicide myth

As the policy center has pointed out previously, it’s important to dispel the holiday-suicide myth because allowing people to think that suicide is more likely during the holiday season can have contagious effects on people who are experiencing a crisis and contemplating suicide. National recommendations for reporting on suicide advise journalists not to promote information that can increase contagion, such as reports of epidemics or seasonal increases, especially when the claim has no basis in fact. The recommendations, which were developed by journalism and suicide-prevention groups along with the Annenberg Public Policy Center, say that reporters should consult reliable sources such as the CDC on suicide rates and offer information about resources that can help people in need.

Too few know about the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Unfortunately, too few people know about a recently created resource for those in crisis. Anyone who is struggling or in crisis, or knows someone who is, should dial 988, the national Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

In July 2022, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline was renamed the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, and 988 was officially implemented as the hotline’s three-digit nationwide telephone number. But panel surveys from the Annenberg Public Policy Center find that only a small percentage of people are familiar with the new 988 number.

When a survey panel of U.S. adults were asked in October 2023 if they know the number to dial to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, 1 in 5 (21%) said yes, only slightly higher than the 16% who said yes in January. In addition, among those who say they know the number only a portion can provide it. Another APPC survey that asked this question in June 2023 found that among those who said they knew the lifeline number, only half could correctly provide it.

Journalists helping to dispel the holiday-suicide myth can provide other resources for readers who are in or know of someone who is in a potential crisis. Those offering valuable information include the CDC, the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

How this media study is conducted

News and feature stories linking suicide with the holidays were identified through searches of the LexisNexis and NewsBank databases combining the term “suicide” with words such as “holiday,” “Christmas” and “New Years,” (with the addition of terms such as “increase” in NewsBank) from November 15, 2022, through January 31, 2023. Researchers determined whether the stories supported the link, debunked it, or made a coincidental reference. Stories with a coincidental reference were eliminated. Only domestic suicides were counted.

APPC’s Sam Fox and Lauren Hawkins supervised the coding of the stories. The coding was done by Penn students Nicholas Bausenwein, Thomas Christaldi, Ginger Fontenot, Sienna Horvath, Nia Peterson, Tara Shilkret, and Julia Van Lare, who are with APPC’s Annenberg Health and Risk Communication Institute.